Thinking about Art Auctions in the 21st Century

- Latest Blog Posts

- Comment on Works

2016-07-02 11:08 - “Man and Sword Becomes One” in Art

2016-05-30 15:25 - How to survive for traditional art galleries in today's e-business?

2016-07-12 20:21 - Klimt's Painting and the Film by Same Name: Woman in Gold

2016-06-18 16:46 - There is nothing quite as inspiring as the bold serenity of the mountain art

2016-05-13 17:43 - Dali: the only difference between me and a madman is that I am not mad

2016-05-13 17:37 - Rococo art is an 18th-century artistic movement

2016-05-13 17:34 - Definition of African Art

2016-05-13 17:32

- Singing Palette > Art Blog > Singing Palette's Blog > Thinking about Art Auctions in the 21st Century

- Thinking about Art Auctions in the 21st Century

- Singing Palette2016-10-16 19:56

- View Artworks by Singing Palette >> Home of Singing Palette's Blog >>

- -- Dan Petley, UK

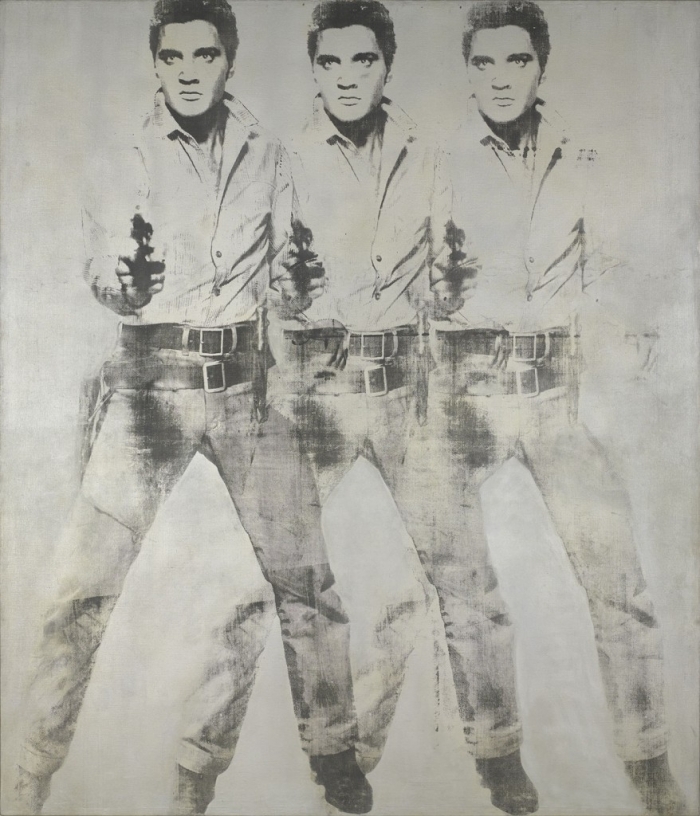

- When I was unfamiliar with the world of art auctions, I would insist that the within its very secretive boundaries paintings were not loved but seen purely as commodities. However, since I have developed a deeper interest I realize that nothing in the art world can ever be summed up quite so easily. My own personal interest in the art market was cemented when I saw Robert Hughes’ documentary ‘The Mona Lisa Curse’ in 2011. It explored soaring auction prices, and the late art critic’s own assertion that the contemporary market was displaying a disturbing trend of people buying and collecting art not through respect for the work’s beauty or cultural significance, but because they expected a financial return on their investment.Some of Hughes’ very convincing thesis took evidence from ‘Beautiful Inside My Head Forever’, Damien Hirst’s September 2008 auction at Sotherby’s in London, where much of the excitement in the art world wasn’t just for the prices Hirst’s art went for, but for other (still financial) factors. Many doubted that in just 24 hours the market could absorb 223 lots (including many ‘spot’ paintings made purely by assistants) from one living artist. The fact that 97% of the works sold was big news, as was the event bringing in a staggering $198 million, expanding the market by attracting new buyers (almost 40% of buyers were new to the art market). In retrospect, amongst all these stark figures, the sale is seen as even more significant due to it taking place just before the economic crash.A year later Hirst’s stock in the market had shrunk, and around 2012, this unprecedented deflation continued with his works reselling at an average loss of 30%. The art market is a rich person's game played according to rich people's rules, which thrives on secrecy. Who knows, Hirst and his advisors could well have orchestrated this whole situation to maximize his profits when his work was at its peak?Certain philistines would call the art market a bubble economy, where asset prices rise significantly above the fundamental value of that asset suggesting that it’s purely a high-end media circus that creates fortunes out of nothing. However, if you took any renaissance painting and sold it for what the individual elements were worth, some nice wood with a bit of oil stuck to it, they would be worth around $60 if you’re lucky.This is where art valuation comes in, the estimation of potential market value of works of art. Despite being more about finance than an aesthetic concept, artworks are cultural entities, so subjective views of cultural value are vital in the process of selling them. Whereas a work’s market value is arrived at by comparing data from various sources such as auction houses, curators and specialized market analysis, cultural value is almost an abstract term in comparison. I think the question of how one calculates cultural value opens an even more interesting inquiry, how can cultural value be proven?Arguably, it can’t. Like I said earlier it is never easy to sum up the art world in simple terms. You could argue that this simultaneously proves and invalidates Robert Hughes’ point. A trend has indeed developed since the 60s where auction houses and collectors could be investing in novelty and trendiness as opposed to beauty or cultural significance. However, the fact that these factors can’t be proved, only debated is arguably what makes the art market so compelling.In ‘The Mona Lisa Curse’ Hughes does insist that apart from drugs, art is the biggest unregulated market in the world, which does imply that the venture capitalists dealing in art are taking serious risks with their investments.Something that has to be addressed is the posthumous career of Andy Warhol. In his lifetime Warhol never sold a painting for more than $50,000, but since his death in 1987 prices for his work have progressively rocketed, and seeing as his art factory was so prolific there has never been a shortage of works to sell. On November 11th 2014, two Warhol portrait screen prints, ‘Triple Elvis’ and ‘Four Marlons’ sold for $81.9 million and $69.6 million respectively, at Christie's New York sale of postwar and contemporary art.In ‘The Mona Lisa Curse’, Hughes had used the relationship between Warhol’s work and the art market to demonstrate connections between high profile exhibitions of old masters in the 60s and Warhol’s factory process. He considers this trend to have developed to the prices of living artists’ work becoming somewhat unbelievable when the post-recession documentary was broadcast.The best known collector of Warhol is Alberto Mugrabi, who is confronted by Hughes in the documentary. One way of looking at Warhol’s popularity among collectors is that the market has filled a void created by the decline of critical authority. Although Hughes makes some convincing points, his criticism of Warhol, and more importantly Mugrabi’s obsession with him does seem to fall flat, as it sounds as though he is criticizing Warhol because his work has continued to become so popular.The main telling factor I see in the popularity of Warhol is that a trend for his work has caused the market to alter. I have a real passion for old master paintings, so let’s finish by comparing their change in value compared to that of Warhol’s since the economic crash.Consider how in 2002 ‘The Massacre of the Innocents’ firmly attributed to Peter Paul Rubens was sold for a then record price of over $77 million at Sotheby's in London. This headline grabbing sale set a world record price for a Rubens, and was then the third most expensive painting ever sold. This figure sits right between the prices for the two Warhols I mentioned earlier.Compare this to an evening sale at Christie’s in London last week, raising just over $8 million on all lots featuring works by Hans Hoffmann and Brueghel the Younger, below half the presale low estimate of $19.29 million. Only 58% of works on offer sold.As the 21st century has progressed, wealthy collectors’ interest in old masters has become superseded by investment in instantly recognizable works by ‘brand’ contemporary artists like Hirst. It is quite easy to draw links to collectors’ interest in Warhol, where a seemingly bottomless pit of production line pieces has developed rather than damaged his work’s ‘must have’ status. This could imply that old masters have fallen out of fashion not just because they guarantee less instant return on investment, but they are simply no longer fashionable. Another reason could be that authorship of old master paintings is often open to question, a problem that’s avoided by buying modern and contemporary pieces attributed to an artist during their lifetime.A true lover of art would agree that an attribution is unnecessary to make a painting uplifting and magical. As the old masters slump continues, there are some amazing historical paintings which are failing to find collectors, meaning the stage is set for more connoisseurs to jump into this neglected side of the market. The more modest prices, which continue to contract while the contemporary market expands, should have attracted more investors over the last few years. So has the contemporary market crushed the old masters? Has fashion killed romance?Not at all. The market has to wax and wane in an unpredictable fashion, it is the nature of the beast. The post war and contemporary art market bubble has to burst, significantly lowering the value of this work. It’s not a question of if this will happen, but when. Arguably, collectors of old master paintings can rest assured that their assets will always have a value, albeit still an unpredictable one, due to their unshakable cultural significance.I believe the art market, love it or hate it, triggers discussions in the press about paintings, which allow the public to feel more engaged. I’d argue that this is in fact strengthened by the fact these great works are monotonously examined in financial terms as this reinforces their glamour, making the secretive discussions of cultural value that happen behind closed doors even more enigmatic. If you ask me, this situation where the love of art itself is expressed as a fluctuating commodity is the real romantic mystery, as it achieves more in underlining the civilizing significance of great art than we’re generally willing to accept.

- Copyright Statement: members bear all the responsibilities for what you're posted.

All the reproduction of any forms about this work unauthorized by Singing Palette or the blogger including images, texts and so on will be deemed to be violating the Copyright Laws.

To cite this webpage, please link back here.

Singing Palette

Singing Palette