Four Apostles

Albrecht Durer

- Price: Price on Request

- Art Type: Oil Painting

- Size:

- English Comments: 0

- International Comments: 0

- Creating Date:

- Introduction and Works of Albrecht Durer >>

Keywords:

Apostles

Work Overview

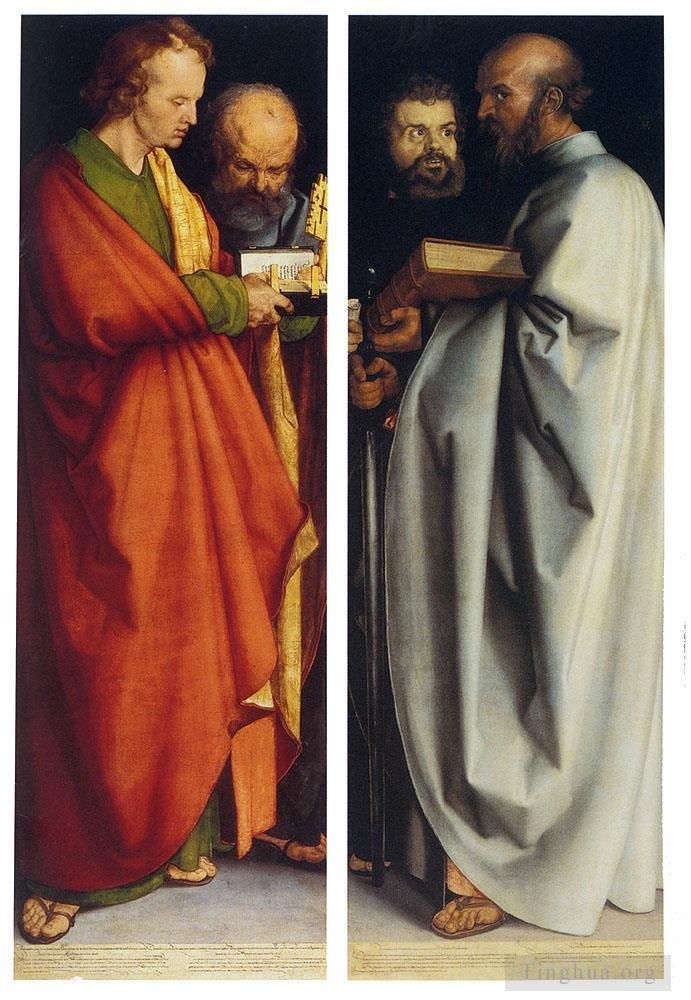

- The Four Apostles

Albrecht Dürer

1526

Each panel 215 cm x 76 cm (85 in x 30 in)

oil on lindenwood

Alte Pinakothek, Munich

The Four Apostles is a panel painting by the German Renaissance master Albrecht Dürer. It was finished in 1526, and is the last of his large works. It depicts the four apostles larger-than-life-size. The Bavarian Elector Maximilian I obtained The Four Apostles in the year 1627 due to pressure on the Nuremberg city fathers. Since then, the painting has been in Munich and, despite all the efforts of Nuremberg since 1806, it has not been returned.

When Dürer moved back to Nuremberg he produced many famous paintings there, including several self-portraits. He gave The Four Apostles to the town council. Saints John and Peter appear in the left panel; the figures in the right panel are Saints Mark and Paul. Mark and Paul both hold Bibles, and John and Peter are shown reading from the opening page of John's own Gospel. At the bottom of each panel, quotations from the Bible are inscribed.[1]

The apostles are recognizable by their symbols:

St. John the Evangelist: open book

St. Peter: keys

St. Mark: scroll

St. Paul: sword and closed book

They are also associated with the four temperaments.

St. John: sanguine

St. Peter: phlegmatic

St. Mark: choleric

St. Paul: melancholy

The Four Apostles was created during the Reformation, begun in 1517 and having the largest initial impact on Germany. As it was a Protestant belief that icons were contradictory to the Word of God, which was held in the utmost supremacy over Protestant ideas, the Protestant church was not a patron of any sacred art. Therefore, any Protestant artist, like Dürer became, had to commission their own works. Many aspects of the image depicted prove significant in light of the Reformation itself.

--------------------------------------

The customary title of the painting, Four Apostles, is somewhat misleading, since only three of the four men depicted—Saints John, Peter, and Paul—were, strictly speaking, apostles. The fourth, St. Mark, though an evangelist, was traditionally thought to be a disciple of the Apostle Peter. Currently housed in the Alte Pinakothek museum in Munich, Dürer’s masterpiece represents one of his greatest achievements.

The significance of Dürer’s donation to the Nuremberg magistrates (who had formally adopted the Reformation only a year and a half earlier) as well as the interpretation of the iconography and inscriptions have been the subject of much debate. What were Dürer’s intentions in presenting such an expensive and monumental work to the town councilors, rather than to the church? Was this a genuine gift or a sale — seeing as Dürer received payment of 100 gulden from the magistrates, who insisted that he be compensated?

Questions surrounding the meaning of the subject matter have been even more vexed. While the visual content of the painting seems a clear indication of evangelical sympathies, what is the reason for the inscriptions, which warn against false teachers and prophets (2 Peter 2:1–3 and 1 John 4:1–3), rampant immorality (2 Timothy 3:1-7), and religious hypocrites (Mark 12:38–40 — a passage similar to today’s Gospel text in Matthew 23:1–12)? After reviewing the rich body of literature that has sought to answer these questions, historian Carl C. Christensen argues that, despite a current lack of consensus on the meaning of the inscriptions, Dürer’s painting nevertheless represents “the personal witness of the artist for his biblically based Christianity.”

Christensen’s conclusion that “it is the primacy of the Word, above all, that is the message of Four Apostles” is clearly borne out in the visual components and their arrangement. Three of the figures hold scripture: Paul holds a closed, entire Bible, while Mark holds a scroll of his Gospel, and John reads a book containing his Gospel — open to the first verse, which Dürer has included in Luther’s German rendering: “Am Anfang war das Wort” — in the beginning was the Word.

But what, you may ask, is the Word of God, when there are so many words of God: the whole Bible, Old and New Testament? The Gospel accounts of Jesus? The Second Person of the Trinity who was “in the beginning”? It was this question that Martin Luther posed at the beginning of his 1520 treatise, Freedom of a Christian. His answer, spelled out in that treatise and other writings, such as the biblical prefaces he wrote for his German Bible, constitutes one of his most important but frankly most misunderstood legacies. Dürer’s painting captures visually what is truly distinctive about yet sometimes overlooked in Luther’s evangelical understanding of the Word and the nature of biblical authority.

Fundamental to Luther’s understanding of the Word of God is a division between promises and commandments, or “law” and “gospel.” While both are Word of God, the gospel is the Word in a special sense, and for two reasons. First, it creates the faith that justifies. In the preface he wrote for his 1522 German New Testament, Luther defines the “gospel” as any preaching about the benefits of Christ found or promised anywhere in the Bible. However, he notes, this message is particularly clear in John’s Gospel, the epistles of Paul (especially Romans), and the first epistle of Peter. These books “are the books that show you Christ and teach you all that is necessary and salvatory for you to know, even if you were never to see or hear any other book or doctrine.”

Second, because of what it does, the gospel becomes for Luther an interpretive principle: the key for interpreting and evaluating the entire scripture. In his preface to the books of James and Jude in his German New Testament, he writes, “All genuine sacred books agree in this, that all of them preach and inculcate [treiben] Christ. And that is the true test by which to judge all books, when we see whether or not they inculcate Christ. For all the Scriptures show us Christ…”

Scripture, as God’s word, is then a kind of performative speech (like the baptismal formula); most effectively, scriptural preaching is performative speech that puts forth Christ and creates faith. For Luther, the Bible is Word of God not just because of what it says but also because of what it does: it sets forth Christ in such away as to awaken faith in us. And those parts of scripture that do this pre-eminently are especially esteemed and function as the internal criterion for interpreting the rest of scripture.

There is no iconographic tradition before Dürer for portraying these four biblical writers together, but in light of Luther’s views on the primacy of the gospel and where it is especially to be found, the logic of the figures as well as their arrangement is easily grasped. John on the left and Paul on the right dominate the composition, larger and lighter than Peter and Mark in the background. Their robes partially obscure the other figures, even as the books they hold mediate access to them. Peter was not only the presumed author of the epistle prized by Luther along with the writings of Paul and John; he was also the apostle to whom the keys of the church had been given and the predecessor of the Pope. He is here subordinated to John and reads in John’s Gospel for guidance. Of the other three evangelists, Mark is the one whose Gospel begins with direct mention of the gospel message: “The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, the Son of God” (Mark 1:1). Yet he, too, author of a great many of the deeds of Christ, needs to look to Paul, whose clear articulation of the gospel provides the key not only to Mark but to testing all the rest of scripture.

Luther was not the first to assert the authority of scripture — not by a long shot. But he drew an unprecedented conclusion from the traditional esteem for the Bible as Word of God that marked a new moment in Christian understandings of the Bible as God’s living Word. With the Christian tradition before him and much of it since, Luther affirmed that scripture contained the Word of God. But for Luther and others of his theological descendents, the written scriptures are important not just for what they contain but in addition — or even rather — for what they convey: the Word Incarnate, Jesus Christ, to be grasped in faith — God’s Word, as Paul writes to the Thessalonians, “which is also at work in you believers.” Through his choice of biblical figures, their arrangement, and especially the dialectical positioning of the entire Bible and the opening verse of John’s Gospel, Dürer renders Luther’s discerning insight about God’s living Word and where it is found into powerful visual idiom.

Dürer did not paint these four paintings on commission. It was he who wanted to donate them to Nuremberg, his native city. On 6 October 1526 the artist offered The Four Holy Men to the city fathers of Nuremberg: `I have been intending, for a long time past, to show my respect for your excellencies by the presentation of some humble picture of mine as a remembrance; but I have been prevented from so doing by the imperfection and insignificance of my works... Now, however, that I have just painted a panel upon which I have bestowed more trouble than on any other painting, I considered none more worthy to keep it as a memorial than your excellencies.' As it was common in many cities in Italy to bestow the town hall with a work of art that would serve as an example of buon governo, so did Dürer want to provide his native city with a work of his that had been purposefully made to this end.

The council gratefully accepted the gift, hanging the two works in the upper government chamber of the city hall. Dürer was awarded an honorarium of 100 florins. The four monumental figures remained in the municipality of Nuremberg until 1627, when, following threats of repression, they had to be sold to the elector of Bavaria, Maximilian I, a great enthusiast of Dürer's work. On that occasion, however, the prince had the inscriptions, at the bottom of the paintings, sawed off and sent back to Nuremberg, as they were considered heretical and injurious to his position as the sovereign Catholic. The city handed them over to the museum in Munich in 1922, where they were rejoined with their respective panels.

Despite the presence of the Evangelist Mark, the pair of panels with their slightly larger than life-size figures have since the 1530s usually been called `The Four Apostles', although The Four Holy Men is a more accurate title. John the Evangelist stands on the far left, holding an open New Testament from which he is reading the first verses of his Gospel. Behind him is the figure of Peter, holding the golden key to the gate of heaven. On the other panel, standing at the back, is the Evangelist Mark, with a scroll. On the far right is Paul, holding a closed Bible and leaning on the sword - a reference to his subsequent execution.

The Four Apostles, witnesses to the faith, were to simultaneously function as a warning. For this, their figures had inscriptions affixed that the calligrapher Johann Neudörfer had added to the bottom of the panels, which reproduced biblical passages from the recent translation of Martin Luther (1522). The first line of both are references to the Apocalypse of St John (22:18 ff.), but the essential content has another origin: it is a reproach to the secular powers not to conceal the divine word in seductive human interpretation. Besides, it reads that everyone should take the warning of the "four excellent men" to heart: almost a formulation of the symbolic program represented in the choice of the four figures, of three apostles and an evangelist, Mark, an unusual choice that Dürer does not explain or illustrate.

The Four Apostles undoubtedly represents his personal religious credo through the inscriptions. His position is to be on guard against the "false prophets." This becomes understandable if one considers the political-religious background of that time and the violence and passion of the religious upheavals, which favoured the onset of false doctrines. Dürer knew that his support of the Lutheran movement, which surely came out from the words of the inscriptions, would have been shared by important and influential citizens; in fact, different from the majority of Nuremberg sovereignties, firmly embraced Protestantism in toto.

In his Bulletin on the Artists and Artisans in Nuremberg of 1546, the aforementioned Neudörfer writes that Dürer wanted to represent a sanguine, a choleric, a phlegmatic, and a melancholic. It is possible to subdivide them according to the following attributions: John would be the sanguine, Peter the phlegmatic, Paul the melancholic, and Marco the choleric. In addition, each temperament would correspond to one of the four ages of life. Preparatory drawings exist for the heads in Berlin and Bayonne .

Although some scholars had believed that the two figures at the back of the pictures, Peter and Mark, had been added later by Dürer, a technical analysis in the 1960s showed that the paintings had originally been conceived with the four men. This examination also confirmed that they were made as a pair, not as wings of a triptych.

These are Dürer's last known oil paintings, done when he was 55. They represent his spiritual testimony and are among his most powerful works.

- Copyright Statement:

All the reproduction of any forms about this work unauthorized by Singing Palette including images, texts and so on will be deemed to be violating the Copyright Laws.

To cite this webpage, please link back here.

- >> English Comments

- >> Chinese Comments

- >> French Comments

- >> German Comments

- >>Report

- Emperor Charlemagne

- Virgin Suckling the Child

- Emperor Charlemagne and Emperor Sigismund

- The Apostles Philip and James

- The Cross

- Salvator Mundi

- The Dresden Altarpiece

- St Peter

- Portrait of Emperor Maximilian I

- Alliance Coat of Arms of the Durer and Holper Families

- Portrait of Jacob muffle

- Saint Jerome (St Jerome in the Wilderness)

- Paumgartner Altar right wing

- Portrait of St Sebastian with an Arrow

- Portrait of a Boy with a Long Beard

- Adam and Eve

- The Jabach Altarpiece

- Suicide of Lucretia

- The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin

- Portrait of Oswolt Krel full

- Self-Portrait (Portrait of the Artist Holding a Thistle)

- Four Apostles

- Portrait of a Young Man

- Lots escape

- Portrait of a Man 1504

- Portrait of Hieronymus Holzschuher

- St Jerome

- Twelve year old Jesus in the Temple

- Circumcision of Jesus (Seven Sorrows The Circumcision)

- John

- Christ as the Man of Sorrows

- Holy Family

- The Dresden Altarpiece central panel

- Christ among the Doctors

- Sylvan Men with Heraldic Shields Albrecht Durer

- Job and His Wife

- Maria with child

- The Four Apostles left part St John and St Peter

- The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin The Flight into Egypt

- Portrait of Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony

- Paumgartner Altar left wing

- Portrait of Elsbeth Tucher

- The Virgin Mary in Prayer

- Ecce Homo

- Portrait of Barbara Durer

- The Madonna of the Carnation

- Portrait of a Young Furleger with Her Hair Done Up

- Combined Coat of Arms of the Tucher and Rieter Families

- Paumgartner altarpiece

- Portrait of a Young Furleger with Loose Hair

- Adoration of the Trinity (Landauer Altarpiece)

- Portrait of Durers Father at 70

- Portrait of a Man 2

- Two Musicians

- The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin Mother of Sorrows

- Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman

- Felicitas Tucher nee Rieter

- Albrecht Portrait of a Man

- Self-Portrait (Self-Portrait with Fur-Trimmed Robe)

- Virgin and Child before an Archway

- Madonna and Child Haller Madonna

- Virgin and child holding a half eaten pear

- The Dresden Altarpiece side wings

- Lot and His Daughters (Lot Fleeing with his Daughters from Sodom)

- Madonna with the Siskin

- Drummers and pipers

- Self-Portrait at 26

- Face a young girl with red beret

- Hans Tucher

- The flight to Egypt Softwood

- Lamentation of Christ

- Hercules kills the Symphalic Bird

- Portrait of the Elder

- Seven Sorrows Crucifixion

- Eve Renaissance

- Avarice

- Virgin and Child with Saint Anne

- Adoration of the Magi

- Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand

- The Lady of the festival du Rosaire

- Emperor Sigismund

- Sylvan Men with Heraldic Shields

- Portrait of Oswolt Krel

- Lamentation for Christ

- The Wire-Drawing Mill

- Primula

- The tuft of grass MINOR

- Garza

- The Little Owl

- Crucifixion

- Cervus Lucanus

- View of Nuremberg

- Lobster

- The Holy Family in a Trellis

- Nuremberg Woman Dressed for Church

- The Castle at Trento

- Innsbruck

- House by a Pond

- Head of an Angel

- Courtyard of the Former Castle in Innsbruck with Clouds

- Lion

- Iris

- Hands

- Hand

- Cupid the Honey Thief

- Self portrait at 13

- View of the Arco Valley in the Tyrol

- Head of a Stag

- The Trefileria on Peignitz

- Arion 2

- Arion

- Knight On Horseback

- A Young Hare

- The Trefileria on Peignitz 2

- Pond in the wood

- Dry dock at Hallerturlein Nuremberg

- Willow Mill

- The Prodigal Son

- View of Kalchreut

- Saint John Church

- Iris Troiana

- The Fall

- Doss Trento

- Innsbruck Seen from the North

- Hare

- Tilo on the cantilever of a bastion

- Courtyard of the Former Castle in Innsbruck without Clouds

- Dead Bluebird

- Map of the Southern Sky

- The city of Trento

- Three Mighty Ladies from Livonia

Singing Palette

Singing Palette