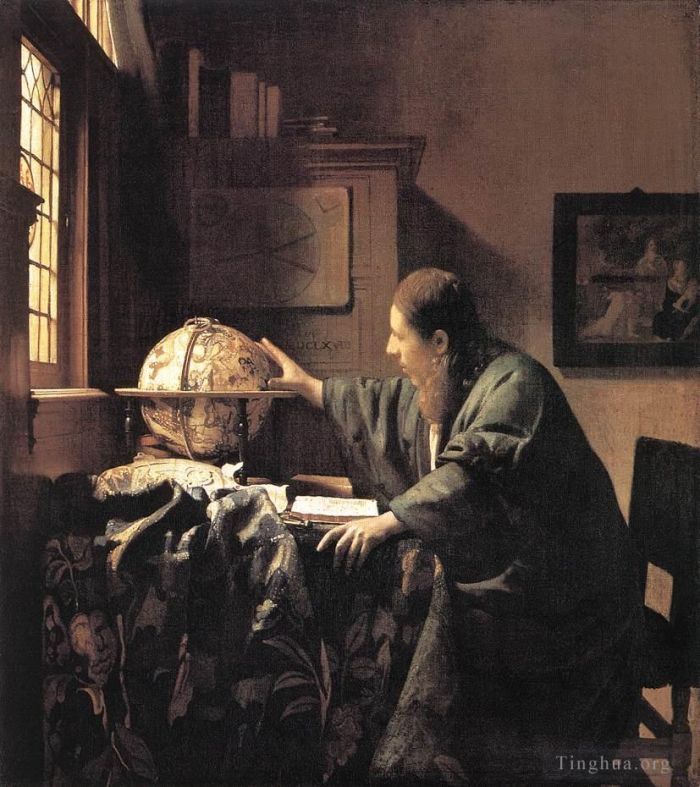

The Astronomer

Johan Vermeer

- Price: Price on Request

- Art Type: Oil Painting

- Size:

- English Comments: 0

- International Comments: 0

- Creating Date:

- Introduction and Works of Johan Vermeer >>

Keywords:

Astronomer

Work Overview

- The Astronomer

Artist Johannes Vermeer

Year c. 1668

Medium Oil on canvas

Dimensions 51 cm × 45 cm (20 in × 18 in)

Location Musée du Louvre, Paris

The Astronomer is a painting finished in about 1668 by the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer. It is oil on canvas, 51 cm x 45 cm (20 x 18 in), and is on display at the Louvre, in Paris, France.[1]

Portrayals of scientists were a favourite topic in 17th-century Dutch painting[1] and Vermeer's oeuvre includes both this astronomer and the slightly later The Geographer. Both are believed to portray the same man,[2][3][4] possibly Antonie van Leeuwenhoek.[5] A 2017 study indicated that the canvas for the two works came from the same bolt of material, confirming their close relationship.[6]

The astronomer's profession is shown by the celestial globe (version by Jodocus Hondius) and the book on the table, the 1621 edition of Adriaan Metius's Institutiones Astronomicae Geographicae.[2][3][4][7] Symbolically, the volume is open to Book III, a section advising the astronomer to seek "inspiration from God" and the painting on the wall shows the Finding of Moses—Moses may represent knowledge and science ("learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians").

The provenance of The Astronomer can be traced back to 27 April 1713, when it was sold at the Rotterdam sale of an unknown collector (possibly Adriaen Paets (nl) or his father, of Rotterdam) together with The Geographer. The presumed buyer was Hendrik Sorgh, whose estate sale held in Amsterdam on 28 March 1720 included both The Astronomer and The Geographer, which were described as ‘Een Astrologist: door Vermeer van Delft, extra puyk’ (An Astrologist by Vermeer of Delft, topnotch) and ‘Een weerga, van ditto, niet minder’ (Similar by ditto, no less).

Between 1881 and 1888 it was sold by the Paris art dealer Léon Gauchez to the banker and art collector Alphonse James de Rothschild, after whose death it was inherited by his son, Édouard Alphonse James de Rothschild. In 1940 it was seized from his hotel in Paris by the Nazi Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg für die Besetzten Gebiete after the German invasion of France. A small swastika was stamped on the back in black ink. The painting was returned to the Rothschilds after the war, and was acquired by the French state as giving in payment of inheritance taxes in 1983[9][10] and then exhibited at the Louvre since 1983.

In view of the fact that the Astronomer and the Geographer are probably pendants, and are the only works in Vermeer's oeuvre that represent male figures involved in scholarly pursuits, we are treating them conjointly.

Until 1778, they remained together. The signatures and dates on both paintings are questionable, but they must have been executed toward the end of the 1660s.

None of these paintings appears in the sale of 1696, and were therefore commissioned by a patron who was especially interested in astronomy or the celestial sciences. In both paintings, the references to books, scientific instruments, and, in the portrait of the Astronomer, the celestial globe by Jodocus Hondius, are accurately depicted.

The latter painting features on the rear wall a picture representing the scene of the finding of Moses, which has been interpreted as being associated with the advice of divine providence in reaching, in the case of the astronomer, for spiritual guidance.

Although farfetched, it is likely that the content of the painting is associated in some way with the meaning of the work. The sea chart on the wall of the Geographer does not have any religious association. It must be remembered that the rise of interest in scientific research at the time, fostered by the newly established University of Leyden, and philosophers like Descartes, did not have any specific religious associations. Quite to the contrary, the aim was to explore the universe, and simultaneously to further Dutch navigation in its conquest of faraway lands.

Both paintings, with their interiors of scholarly studios and scientific paraphernalia, award Vermeer the opportunity for lightening effects that envelop the scientists in the mystery of an atmosphere that lifts their occupations into the realm of spirituality.

-------------------------

“What is it about Johannes Vermeer?” contemporary art lovers and historians ask. The enigmatic painter, apparently well known in his day, lapsed into obscurity after his death only to surface again in the 19th century and capture the imagination and esthetic taste of modern times. Even though he produced no more than 40 paintings, their originality and refinement place him among the greatest 17th-century Dutch artists (1).

Vermeer’s life story can only be patched together from public records, and no portrait is available of his physical appearance. He was sufficiently trained in his trade to belong to an artists’ guild and was esteemed enough by his colleagues to be twice appointed guild leader. Nonetheless, financial hardship, aggravated by his inability to support a brood of 15 children, 11 of whom survived to adulthood, limited his artistic output. He made little money from his paintings and died poor at age 43 (2). “Because of…the large sums of money we had to spend on the children, sums he was no longer able to pay,” his wife lamented after his death, “he fell into such a depression and lethargy that he lost his health in the space of one and a half days and died” (3).

Though untraveled, Vermeer was well connected with other artists, including Gerald Ter Borch and Dirk van Baburen, and might have been influenced by Caravaggio and Carel Fabritius, the brilliant student of Rembrandt. Vermeer’s work is also reminiscent of 15th-century Flemish art, especially in the use of color and meticulous detail; however, he brought to these elements unique sensitivity and novelty (4).

During the 17th century, the arts broke away from classical style into genre (scenes of everyday life). Vermeer’s work assumed the domestic intimacy of the Dutch school yet moved beyond its monochromatic, evenly lit, raucous gatherings. Although more than any of his contemporaries Vermeer saw poetry in everyday activities (The Lacemaker, The Procuress, The Milkmaid), his characters had an air of introspection and seemed to be engaged in more than the activities themselves. In scenes of extraordinary simplicity and clarity, he placed solitary figures, whose dimensions were sometimes enlarged in relation to the surroundings, within the confines of carefully constructed spaces (1). Then, elaborating on textures and details, he used light to peer through the external trappings into the soul.

While the arts were abandoning classical themes for scenes of everyday life, the sciences were inventing new methods of inquiry, dispelling the shadows of antiquity to view the world through a lens. Newton was making the first reflecting telescopes, Louis XIV was building an observatory in Paris, and Huygens had detected the first moon of Saturn (5,6). An innovator himself, Vermeer was likely acquainted with the science of his time and is often linked with Anton van Leeuwenhoek, Dutch inventor of the microscope. Van Leeuwenhoek, a merchant who sold cloth not far from Vermeer’s abode in Delft and who later became the court-appointed executor of the artist’s will, discovered through his microscope the cellular nature of spermatozoa and bacteria and was skilled in navigation, astronomy, and mathematics. Van Leeuwenhoek, who was born the same year as Vermeer, may have inspired both The Astronomer (on this month’s cover of Emerging Infectious Diseases) and its companion, The Geographer (c.1668–1669) (3).

The Astronomer harmonizes space, color, and light to convey a single human activity, a unified moment in time. Perfectly staged, the scene is a subtle composite of interlocking diagonal, rectangular, or elliptical fields and has no empty or undefined surface. The composition is not narrative but rather forms the context of a sole figure, frozen in a pose of profound preoccupation.

Like many Vermeer characters, the astronomer is placed near a window on the onlooker’s left, which casts a glow on the man of science, revealing youthful freshness, sudden insight, and nervous anticipation. Expressive hands define the geometric space between the sympathetic figure and the celestial globe (drafted by Dutch cartographer Jodocus Hondius in 1600) and drive the forward movement of the body. The desk, framed by a thick tapestry, holds an astrolabe (precursor of the sextant) and a book. On the wall is a circular figure with radial lines.

The moment of discovery reflected on the astronomer’s face captures centuries of human fascination with the universe. The generic physiognomy, unremarkable features, untended hair, and drab attire draw the eyes to the illuminated face of the thinker, in a room where the only light is that of knowledge.

A model to all stargazers, old and new, Vermeer’s scientist reaches beyond the globe at hand into the mysterious continuum of time and space, charting, measuring, counting, categorizing, naming, recording. His contemporary counterpart, whether an astronomer exploring the cosmos or a biologist investigating the microcosm, is still guided by the light of discovery. Uncharted in Vermeer’s days, the spatial distribution of disease follows the evolution over time of agent, host, and environment and is the domain of those today who trace the time-space continuum of emerging pathogens, from Ebola to influenza and SARS.

- Copyright Statement:

All the reproduction of any forms about this work unauthorized by Singing Palette including images, texts and so on will be deemed to be violating the Copyright Laws.

To cite this webpage, please link back here.

- >> English Comments

- >> Chinese Comments

- >> French Comments

- >> German Comments

- >>Report

- The Astronomer

- The Guitar Player

- The Art of Painting (The Allegory of Painting or Painter in his Studio)

- The Concert

- Diana and her Nymphs

- Young Girl with a Flute

- The Milkmaid (The Kitchen Maid)

- Saint Praxidis

- The Lacemaker

- View of Delft

- Allegory of the Catholic Faith

- A Lady Drinking and a Gentleman

- Woman with a Lute

- Girl with the Red Hat

- Mistress and Maid

- Woman with a Pearl Necklace

- Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

- The Geographer

- The Love Letter

- The Girl with the Wine Glass (A Lady and Two Gentlemen)

- Officer And Laughing Girl

- Lady Seated at a Virginal

- Girl with a Pearl Earring

- The Procuress

- Study of a Young Woman

- Christ in the House of Mary and Martha

- Girl Interrupted at Her Music

- Young Woman with a Water Pitcher

- Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid

- Woman Reading a Letter

- Woman Holding a Balance

- The Glass Of Wine

- A Lady Writing a Letter

- A Maid Asleep

- View of Houses in Delft known as The Little Street

- A Lady at the Virginals with a Gentleman

Singing Palette

Singing Palette