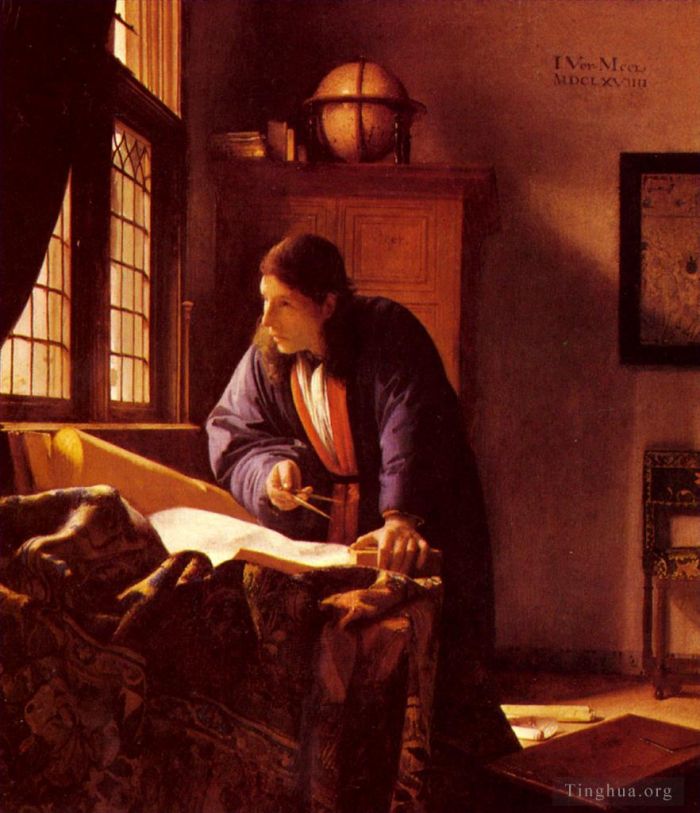

The Geographer

Johan Vermeer

- Price: Price on Request

- Art Type: Oil Painting

- Size:

- English Comments: 0

- International Comments: 0

- Creating Date:

- Introduction and Works of Johan Vermeer >>

Keywords:

Geographer

Work Overview

- The Geographer

El geógrafo

Artist Johannes Vermeer

Year c. 1668–1669

Medium Oil on canvas

Dimensions 52 cm × 45.5 cm (20 in × 17.9 in)

Location Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt

The Geographer is a painting created by Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer in 1668–1669, and is now in the collection of the Städelsches Kunstinstitut museum in Frankfurt, Germany. It is closely related to Vermeer's The Astronomer, for instance using the same model in the same dress, and has sometimes been considered a pendant painting to it. A 2017 study indicated that the canvas for the two works came from the same bolt of material.

This is one of only three paintings Vermeer signed and dated (the other two are The Astronomer and The Procuress).

The geographer, dressed in a Japanese-style robe then popular among scholars,[2] is shown to be "someone excited by intellectual inquiry", with his active stance, the presence of maps, charts, a globe and books, as well as the dividers he holds in his right hand, according to Arthur Wheelock Jr. "The energy in this painting [...] is conveyed most notably through the figure's pose, the massing of objects on the left side of the composition, and the sequence of diagonal shadows on the wall to the right."[3]

Vermeer made several changes in the painting that enhance the feeling of energy in the picture: the man's head was originally in a different position to the left of where the viewer now sees it, indicating the man perhaps was looking down, rather than peering out the window; the dividers he holds in his hand were originally vertical, not horizontal; a sheet of paper was originally on the small stool at the lower right, and removing it probably made that area darker.[3]

Details of the man's face are slightly blurred, suggesting movement (also a feature of Vermeer's Mistress and Maid), according to Serena Carr. His eyes are narrowed, perhaps squinting in the sunlight or an indication of intense thinking. Carr asserts that the painting depicts a "flash of inspiration" or even "revelation". The drawn curtain on the left and the position of the oriental carpet on the table—pushed back—are both symbols of revelation. "He grips a book as if he's about to snatch it up to corroborate his ideas."[4]

The globe was published in Amsterdam in 1618 by Jodocus Hondius.[3] Terrestrial and celestial globes were commonly sold together, and the celestial globe in The Astronomer "was also a Hondius (Hendrick rather than Judocus)", another indication that the two paintings were created as pendant pieces, according to Cant. The globe is turned toward the Indian Ocean, where the Dutch East India Company was then active. Vermeer used an impasto technique to apply pointillé dots, not to indicate light reflected more strongly on certain points but to emphasize the dull ochre cartouche "frame" printed on the globe. Since the globe can be identified, we know the decorative cartouche includes a plea for information for future editions—reflecting the theme of revelation in the painting.[4]

The cartographic objects surrounding the man are some of the actual items a geographer would have: the globe, the dividers the man holds, a cross-staff (hung on the center post of the window), used to measure the angle of celestial objects like the sun or stars, and the chart the man is using, which (according to one scholar, James A. Welu) appears to be a nautical chart on vellum. The sea chart on the wall of "all the Sea coasts of Europe" has been identified as one published by Willem Jansz Blaeu. This accuracy indicates Vermeer had a source familiar with the profession. The Astronomer, which seems to form a pendant with this painting, shows a similar, sophisticated knowledge of cartographic instruments and books, and the same young man modeled for both. That man himself may have been the source of Vermeer's correct display of surveying and geographical instruments, and possibly of his knowledge of perspective.[3]

Wheelock and others assert the model/source was probably Anthonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723), a contemporary of Vermeer who was also born in Delft. The families of both men were in the textile business, and both families had a strong interest in science and optics. A "microscopist", van Leeuwenhoek was described after his death as being so skilled in "navigation, astronomy, mathematics, philosophy, and natural science ... that one can certainly place him with the most distinguished masteres of the art." Another image of van Leeuwenhoek (by the Delft artist Jan Verkolje) about 20 years later shows a broad face and straight nose, similar to Vermeer's model. At the time Vermeer painted the two works, the scientist would have been about 36 years old. He would have been actively studying for his examination for surveyor, which he passed on February 4, 1669. There is no documentary evidence for any kind of relationship between the two men during Vermeer's lifetime, although in 1676, van Leeuwenhoek was appointed a trustee for Vermeer's estate.[3]

The pose of the figure in Vermeer's painting "takes up precisely the position of Faust in Rembrandt's famous etching" (although facing the opposite direction), according to Lawrence Gowing. Similar arrangements can be found in drawings by Nicolaes Maes.

The significance of the sciences increased by leaps and bounds in the seventeenth century, particularly in Holland. This circumstance is reflected in the fact that scientists and scholars were now much in demand as pictorial motifs. Here is an example. Johannes Vermeer, the famous “fine painter” of Delft with the small œuvre, painted a geographer in his study, bent over his working table and surrounded by the utensils of his erudition. He is alone and does not appear to be expecting visitors – there are papers lying on the floor, and his housecoat is another sign of his withdrawal into the realm of his work. An all-pervasive quietude characterizes the scene; the subject’s right hand pauses in mid-air.

The only “action” takes place behind the geographer’s brow. He is literally bathed in the light of recognition; Vermeer has concentrated the entire atmosphere in this one spot. Still leaning over his papers, compass in hand, the geographer lifts his gaze towards the light flooding in through the window; it is as if the perfect solution to his problem has just dawned on him. At the same time, the painting keeps the content of the geographer’s thoughts to itself.

- Copyright Statement:

All the reproduction of any forms about this work unauthorized by Singing Palette including images, texts and so on will be deemed to be violating the Copyright Laws.

To cite this webpage, please link back here.

- >> English Comments

- >> Chinese Comments

- >> French Comments

- >> German Comments

- >>Report

- The Astronomer

- The Guitar Player

- The Art of Painting (The Allegory of Painting or Painter in his Studio)

- The Concert

- Diana and her Nymphs

- Young Girl with a Flute

- The Milkmaid (The Kitchen Maid)

- Saint Praxidis

- The Lacemaker

- View of Delft

- Allegory of the Catholic Faith

- A Lady Drinking and a Gentleman

- Woman with a Lute

- Girl with the Red Hat

- Mistress and Maid

- Woman with a Pearl Necklace

- Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

- The Geographer

- The Love Letter

- The Girl with the Wine Glass (A Lady and Two Gentlemen)

- Officer And Laughing Girl

- Lady Seated at a Virginal

- Girl with a Pearl Earring

- The Procuress

- Study of a Young Woman

- Christ in the House of Mary and Martha

- Girl Interrupted at Her Music

- Young Woman with a Water Pitcher

- Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid

- Woman Reading a Letter

- Woman Holding a Balance

- The Glass Of Wine

- A Lady Writing a Letter

- A Maid Asleep

- View of Houses in Delft known as The Little Street

- A Lady at the Virginals with a Gentleman

Singing Palette

Singing Palette