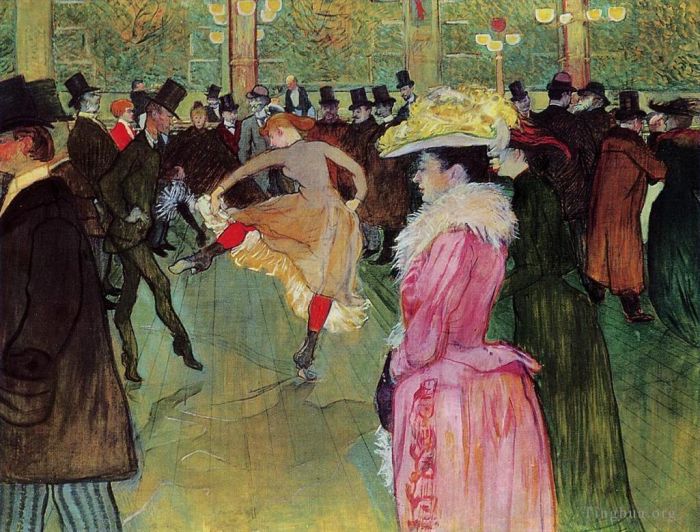

At the Moulin Rouge The Dance

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

- Price: Price on Request

- Art Type: Various Paintings

- Size:

- English Comments: 0

- International Comments: 0

- Creating Date:

- Introduction and Works of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec >>

Work Overview

- At the Moulin Rouge: The Dance

Artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Year 1890

Medium Oil on canvas

Dimensions 115.6 cm × 149.9 cm (45.51 in × 59.02 in)

Location Philadelphia Museum of Art

At the Moulin Rouge, the Dance is an oil-on-canvas painted by French artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. It was painted in 1890, and is the second of a number of graphic paintings by Toulouse-Lautrec depicting the Moulin Rouge cabaret built in Paris in 1889. It portrays two dancers dancing the can-can in the middle of the crowded dance hall. A recently discovered inscription by Toulouse-Lautrec on the back of the painting reads: "The instruction of the new ones by Valentine the Boneless."[1] This means that the man to the left of the woman dancing, is Valentin le désossé, a well-known dancer at the Moulin Rouge, and he is teaching the newest addition to the cabaret. To the right, is a mysterious aristocratic women in pink. The background also features many aristocratic people such as poet Edward Yeats, the club owner and even Toulouse-Lautrec's father. The work is currently displayed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

A recently discovered penciled inscription, in the artist's hand, on the back of this famous painting reads: "The instruction of the new ones by Valentine the Boneless." Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was thus not depicting an ordinary evening at the Moulin Rouge, the fashionable Parisian nightclub but rather a specific moment when a man now known only by his nickname (which certainly describes his nimbleness as a dancer) appears to be teaching the "can-can." Many of the inhabitants of the scene are well-known members of Lautrec's demimonde of prostitutes and artists and people seen only at night including the white-bearded Irish poet William Butler Yeats who leans on the bar. One of the mysteries, however, is the dominant woman in the foreground, the beauty of her profile made all the more so in comparison with that of her chinless companion. It is the latter who expresses better than nearly any other character in this full stage of people Lautrec's profoundly touching ability to be brutally truthful but also truly kind in his observations. Joseph J. Rishel, from Philadelphia Museum of Art: Handbook of the Collections (1995), p. 206.

- Copyright Statement:

All the reproduction of any forms about this work unauthorized by Singing Palette including images, texts and so on will be deemed to be violating the Copyright Laws.

To cite this webpage, please link back here.

- >> English Comments

- >> Chinese Comments

- >> French Comments

- >> German Comments

- >>Report

- The streetwalker

- At the Moulin Rouge the Two Waltzers

- Reclining nude 1897

- The spanish dancer 1888

- Prick and woodman 1882

- Jeanne Wenz

- Nice on the promenade des anglais 1880

- Count alphonse de toulouse lautrec driving a four horse hitch 1881

- Souvenir of auteuil 1881

- Woman in a chemise standing by a bed madame poupoule 1899

- Poupoule in chemise by her bed

- A Laborer at Celeyran

- The toilet ms fabre 1891

- Woman with an umbrella 1889

- Two friends 1895

- At the rat mort 1899

- Madame Lili Grenier

- The redhead with a white blouse 1888

- Woman at her toilette 1889

- Horse and rider with a little dog 1879

- Madame poupoule at her dressing table 1898

- Crouching woman with red hair 1897

- Dun a gordon setter belonging to comte alphonse de toulouse lautrec 1881

- Monsieur boileau 1893

- Margot

- Madame aline gibert 1887

- Artilleryman saddling his horse 1879

- At the races 1899

- Bust of a Nude Man

- Old Man at Celeyran

- Abandonment the pair 1895

- Woman at her toil 1896

- A Corner of the Moulin de la Galette

- Hangover aka The Drinker

- Babylon german by victor joze

- Yvette guilbert 1894

- The medical inspection

- Aristede Bruand at His Cabaret

- Prostitute the sphinx 1898

- The laundryman calling at the brothal 1894

- At the piano madame juliette pascal in the salon of the chateau de malrome 1896

- Cadieux 1893

- The singing lesson the teacher mlle dihau with mme faveraud 1898

- Moulin Rouge

- The jockey 1899

- Troupe de mlle elegantine affiche 1896

- Gustave Lucien Dennery

- Portrait of oscar wilde 1895

- The kiss 1893

- Prostitutes around a dinner table

- The haido 1893

- Louis pascal 1892

- Ambassadeurs aristide bruant in his cabaret 1892

- At the circus fernando the rider 1888

- The bed 1898

- The photagrapher sescau 1894

- Is it enough to want something passionately the good jockey 1895

- Queen of Joy

- May Belfort

- Jane avril dancing 1891

- They woman with a tub 1896

- Jane Avril

- Jane avril leaving the moulin rouge 1893

- Messaline 1901

- Little dog 1888

- Louis Pascal

- Alfred la guigne 1894

- Henri Gabriel Ibels

- The clown cha u kao 1895

- At the Moulin Rouge The Dance

- Booth of la goulue at the foire du trone the moorish dance 1895

- Napol on 1896

- La Goulue at the Moulin Rouge

- Cadieux

- Dancer Adjusting Her Tights

- The motograph 1898

- The clownesse cha u kao at the moulin rouge 1895

- La charrette anglaise the english dog cart 1897

- The promenoir the moulin rouge 1895

- Jane avril 1891

- Portrait of madame de gortzikolff 1893

- Marcelle Lender Dancing the Bolero in Chilpéric

- The coastal bus company 1888

- Coverage of the original print 1893

- La gitane the gypsy 1899

- The journal white poster 1896

- Hunting

- The actor henry samary 1889

- Two friends 1891

- At the circus dressage 1899

- Craftsman modern

- Divan japonais 1893

- A l elysee montmartre 1888

- In bed 1893

- Divan Japonais

- Seated dancer in pink tights 1890

- Messalina seated 1900

- Portrait of vincent van gogh 1887

- The procession of the raja 1895

- The mad cow

- They woman in bed profile getting up 1896

- Ball at the moulin de la galette 1889

- Tauromaquia

- Brothel on the rue des moulins rolande 1894

- Girl in a Fur Mademoiselle Jeanne Fontaine

- Madame misian nathanson 1897

- Jane avril 1893

- The last crunbs 1891

- Confetti 1894

- They cha u kao chinese clown seated 1896

- At the Cafe The Customer and the Anemic Cashier

- Red haired woman seated in the garden of m forest 1889

- The englishman at the moulin rouge 1892

- Helene vary 1889

- Woman pulling up her stockings 1894

- The grand tier 1897

- The cartwheel 1893

- At the circus horse and monkey dressage 1899

- At the opera ball 1893

- Lili Grenier in a Kimono

- In bed the kiss 1892

- The salon de la rue des moulins 1894

- Horsewoman 1899

- Comtesse 1887

- Indian decor 1894

- The box with the guilded mask 1893

- At the foot of the scaffold 1893

- At the nouveau cirque the dancer and five stuffed shirts 1891

- At the cirque fernando rider on a white horse 1888

- At the moulin rouge la goulue with her sister 1892

- Dancing at the moulin rouge 1897

- M delaporte at the jardin de paris 1893

- Nude standing before a mirror 1897

- The ambassadors people chics 1893

- Desire dehau reading a newspaper in the garden 1890

Singing Palette

Singing Palette