The Last Supper

Leonardo da Vinci

- Price: Price on Request

- Art Type: Various Paintings

- Size:

- English Comments: 0

- International Comments: 0

- Creating Date:

- Introduction and Works of Leonardo da Vinci >>

Keywords:

Supper

Work Overview

- Artist Leonardo da Vinci

Year 1494

Medium fresco-secco

Movement Renaissance

Subject Last Supper

Dimensions 460 cm (180 in) × 880 cm (350 in)

Location Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, Italy

Coordinates 45°28′00″N 9°10′15″ECoordinates: 45°28′00″N 9°10′15″E

Commissioned by Ludovico Sforza

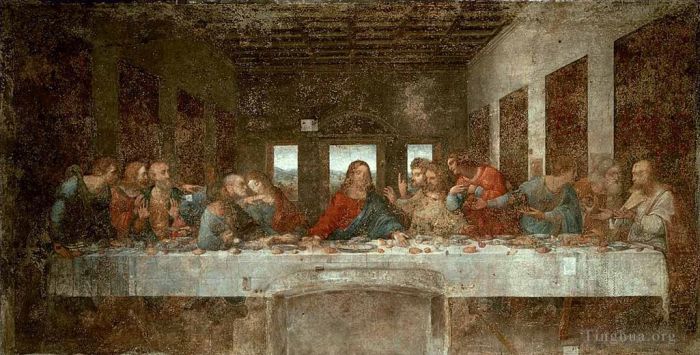

The Last Supper (Italian: Il Cenacolo [il tʃeˈnaːkolo] or L'Ultima Cena [ˈlultima ˈtʃeːna]) is a late 15th-century mural painting by Leonardo da Vinci housed by the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. It is one of the world's most recognizable paintings.[1]

The work is presumed to have been commenced around 1495–1496 and was commissioned as part of a plan of renovations to the church and its convent buildings by Leonardo's patron Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. The painting represents the scene of The Last Supper of Jesus with his apostles, as it is told in the Gospel of John, 13:21. Leonardo has depicted the consternation that occurred among the Twelve Disciples when Jesus announced that one of them would betray him.

Due to the methods used, a variety of environmental factors, and intentional damage, very little of the original painting remains today despite numerous restoration attempts, the last being completed in 1999.

The Last Supper measures 460 cm × 880 cm (180 in × 350 in) and covers an end wall of the dining hall at the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy. The theme was a traditional one for refectories, although the room was not a refectory at the time that Leonardo painted it. The main church building had only recently been completed (in 1498), but was remodeled by Bramante, hired by Ludovico Sforza to build a Sforza family mausoleum.[3] The painting was commissioned by Sforza to be the centerpiece of the mausoleum.[4] The lunettes above the main painting, formed by the triple arched ceiling of the refectory, are painted with Sforza coats-of-arms. The opposite wall of the refectory is covered by the Crucifixion fresco by Giovanni Donato da Montorfano, to which Leonardo added figures of the Sforza family in tempera. (These figures have deteriorated in much the same way as has The Last Supper.) Leonardo began work on The Last Supper in 1495 and completed it in 1498—he did not work on the painting continuously. The beginning date is not certain, as the archives of the convent for the period have been destroyed, and a document dated 1497 indicates that the painting was nearly completed at that date.[5] One story goes that a prior from the monastery complained to Leonardo about the delay, enraging him. He wrote to the head of the monastery, explaining he had been struggling to find the perfect villainous face for Judas, and that if he could not find a face corresponding with what he had in mind, he would use the features of the prior who complained.[6][7]

A study for The Last Supper from Leonardo's notebooks showing nine apostles identified by names written above their heads

The Last Supper specifically portrays the reaction given by each apostle when Jesus said one of them would betray him. All twelve apostles have different reactions to the news, with various degrees of anger and shock. The apostles are identified from a manuscript[8] (The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci p. 232) with their names found in the 19th century. (Before this, only Judas, Peter, John and Jesus were positively identified.) From left to right, according to the apostles' heads:

Bartholomew, James, son of Alphaeus, and Andrew form a group of three; all are surprised.

Judas Iscariot, Peter, and John form another group of three. Judas is wearing green and blue and is in shadow, looking rather withdrawn and taken aback by the sudden revelation of his plan. He is clutching a small bag, perhaps signifying the silver given to him as payment to betray Jesus, or perhaps a reference to his role within the 12 disciples as treasurer.[9] He is also tipping over the salt cellar. This may be related to the near-Eastern expression to "betray the salt" meaning to betray one's Master. He is the only person to have his elbow on the table and his head is also horizontally the lowest of anyone in the painting. Peter looks angry and is holding a knife pointed away from Christ, perhaps foreshadowing his violent reaction in Gethsemane during Jesus' arrest. The youngest apostle, John, appears to swoon.

Jesus

Apostle Thomas, James the Greater, and Philip are the next group of three. Thomas is clearly upset; the raised index finger foreshadows his incredulity of the Resurrection. James the Greater looks stunned, with his arms in the air. Meanwhile, Philip appears to be requesting some explanation.

Matthew, Jude Thaddeus, and Simon the Zealot are the final group of three. Both Jude Thaddeus and Matthew are turned toward Simon, perhaps to find out if he has any answer to their initial questions.

External video

Leonardo, ultima cena (restored) 04.jpg

Leonardo's Last Supper, Smarthistory[10]

In common with other depictions of the Last Supper from this period, Leonardo seats the diners on one side of the table, so that none of them has his back to the viewer. Most previous depictions excluded Judas by placing him alone on the opposite side of the table from the other eleven disciples and Jesus, or placing halos around all the disciples except Judas. Leonardo instead has Judas lean back into shadow. Jesus is predicting that his betrayer will take the bread at the same time he does to Saints Thomas and James to his left, who react in horror as Jesus points with his left hand to a piece of bread before them. Distracted by the conversation between John and Peter, Judas reaches for a different piece of bread not noticing Jesus too stretching out with his right hand towards it (Matthew 26: 23). The angles and lighting draw attention to Jesus, whose head is located at the vanishing point for all perspective lines.

The painting contains several references to the number 3, which represents the Christian belief in the Holy Trinity. The Apostles are seated in groupings of three; there are three windows behind Jesus; and the shape of Jesus' figure resembles a triangle. There may have been other references that have since been lost as the painting deteriorated.

Important copies[edit]

Two early copies of The Last Supper are known to exist, presumed to be work by Leonardo's assistants. The copies are almost the size of the original, and have survived with a wealth of original detail still intact.[11] One copy, by Giampietrino, is in the collection of the Royal Academy of Arts, London, and the other, by Cesare da Sesto, is installed at the Church of St. Ambrogio in Ponte Capriasca, Switzerland. A third copy (oil on canvas) is painted by Andrea Solari (ca. 1520) and is on display in the Leonardo da Vinci Museum of the Tongerlo Abbey, Belgium.

For this work, Leonardo sought a greater detail and luminosity than could be achieved with traditional fresco.[12] He painted The Last Supper on a dry wall rather than on wet plaster, so it is not a true fresco. Because a fresco cannot be modified as the artist works, Leonardo instead chose to seal the stone wall with a double layer of dried plaster.[12] Then, borrowing from panel painting, he added an undercoat of white lead to enhance the brightness of the oil and tempera that was applied on top. This was a method that had been described previously, by Cennino Cennini in the 14th century. However, Cennini had recommended the use of secco for the final touches alone.[13] These techniques were important for Leonardo's desire to work slowly on the painting, giving him sufficient time to develop the gradual shading or chiaroscuro that was essential in his style.

Because the painting was on a thin exterior wall, the effects of humidity were felt more keenly, and the paint failed to properly adhere to the wall. Because of the method used, soon after the painting was completed on February 9, 1498 it began to deteriorate.[12] As early as 1517, the painting was starting to flake, and in 1532 Gerolamo Cardano described it as "blurred and colorless compared with what I remember of it when I saw it as a boy".[14] By 1556—fewer than sixty years after it was finished—Leonardo's biographer Giorgio Vasari described the painting as already "ruined" and so deteriorated that the figures were unrecognizable. By the second half of the sixteenth century Gian Paolo Lomazzo stated that "the painting is all ruined".[12] In 1652, a doorway was cut through the (then unrecognisable) painting, and later bricked up; this can still be seen as the irregular arch shaped structure near the center base of the painting. It is believed, through early copies, that Jesus' feet were in a position symbolizing the forthcoming crucifixion. In 1768, a curtain was hung over the painting for the purpose of protection; it instead trapped moisture on the surface, and whenever the curtain was pulled back, it scratched the flaking paint.

A first restoration was attempted in 1726 by Michelangelo Bellotti, who filled in missing sections with oil paint then varnished the whole mural. This repair did not last well and another restoration was attempted in 1770 by an otherwise unknown artist named Giuseppe Mazza. Mazza stripped off Bellotti's work then largely repainted the painting; he had redone all but three faces when he was halted due to public outrage. In 1796, French revolutionary anti-clerical troops used the refectory as an armory; they threw stones at the painting and climbed ladders to scratch out the Apostles' eyes. The refectory was then later used as a prison; it is not known if any of the prisoners may have damaged the painting. In 1821, Stefano Barezzi, an expert in removing whole frescoes from their walls intact, was called in to remove the painting to a safer location; he badly damaged the center section before realizing that Leonardo's work was not a fresco. Barezzi then attempted to reattach damaged sections with glue. From 1901 to 1908, Luigi Cavenaghi first completed a careful study of the structure of the painting, then began cleaning it. In 1924, Oreste Silvestri did further cleaning, and stabilised some parts with stucco.

During World War II, on August 15, 1943, the refectory was struck by Allied bombing; protective sandbagging prevented the painting from being struck by bomb splinters, but it may have been damaged further by the vibration. From 1951 to 1954, another clean-and-stabilise restoration was undertaken by Mauro Pelliccioli.

The painting's appearance by the late 1970s had become badly deteriorated. From 1978 to 1999, Pinin Brambilla Barcilon guided a major restoration project which undertook to stabilize the painting, and reverse the damage caused by dirt and pollution. The 18th- and 19th-century restoration attempts were also reverted. Since it had proved impractical to move the painting to a more controlled environment, the refectory was instead converted to a sealed, climate-controlled environment, which meant bricking up the windows. Then, detailed study was undertaken to determine the painting's original form, using scientific tests (especially infrared reflectoscopy and microscopic core-samples), and original cartoons preserved in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. Some areas were deemed unrestorable. These were re-painted using watercolor in subdued colors intended to indicate they were not original work, while not being too distracting.

This restoration took 21 years and, on 28 May 1999, the painting was returned to display. Intending visitors were required to book ahead and could only stay for 15 minutes. When it was unveiled, considerable controversy was aroused by the dramatic changes in colors, tones, and even some facial shapes. James Beck, professor of art history at Columbia University and founder of ArtWatch International, had been a particularly strong critic.[15] Michael Daley, director of ArtWatch UK, has also complained about the restored version of the painting. He has been critical of Christ's right arm in the image which has been altered from a draped sleeve to what Daley calls "muff-like drapery".[16]

------------------------------

The Last Supper was painted onto the walls of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie near Milan. Leonardo spent three years painting the work, and much of that time was spent searching the streets of Milan for models of Christ and Judas. It is said that only Leonardo's threats to paint the Prior of the convent as Judas bought him the time he needed to finish.

Although it was common to paint directly onto the walls of building, Leonardo was not trained in this 'fresco' technique, and made a poor choice of materials. This, along with the humid conditions in the convent, meant that the painting began deteriorating while Leonardo was still alive. The refectory has also been flooded and used as a stable - but the painting's luckiest escape came during the Second World War, when the refectory was hit by a bomb. Only some carefully placed sandbags saved this masterpiece from destruction.

There have been many attempts to restore The Last Supper, most of which have done more harm than good. A full restoration was recently completed. It took twenty years - five times longer than Leonardo took to complete the original. However, virtually none of the original paint remains, and critics claim we can no longer regard this as a Leonardo painting.

------------------------------

"Leonardo imagined, and has succeeded in expressing, the desire that has entered the minds of the apostles to know who is betraying their Master. So in the face of each one may be seen love, fear, indignation, or grief at not being able to understand the meaning of Christ; and this excites no less astonishment than the obstinate hatred and treachery to be seen in Judas." (Georgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, 1568; translated by George Bull)

Subject

The subject of the Last Supper is Christ’s final meal with his apostles before Judas identifies Christ to the authorities who arrest him. The Last Supper (a Passover Seder), is remembered for two events:

Christ says to his apostles “One of you will betray me,” and the apostles react, each according to his own personality. Referring to the Gospels, Leonardo depicts Philip asking “Lord, is it I?” Christ replies, “He that dippeth his hand with me in the dish, the same shall betray me” (Matthew 26). We see Christ and Judas simultaneously reaching toward a plate that lies between them, even as Judas defensively backs away.

Leonardo also simultaneously depicts Christ blessing the bread and saying to the apostles “Take, eat; this is my body” and blessing the wine and saying “Drink from it all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for the forgiveness of sins” (Matthew 26). These words are the founding moment of the sacrament of the Eucharist (the miraculous transformation of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ).

Apostles Identified

Leonardo’s Last Supper is dense with symbolic references. Attributes identify each apostle. For example, Judas Iscariot is recognized both as he reaches to toward a plate beside Christ (Matthew 26) and because he clutches a purse containing his reward for identifying Christ to the authorities the following day. Peter, who sits beside Judas, holds a knife in his right hand, foreshadowing that Peter will sever the ear of a soldier as he attempts to protect Christ from arrest.

Suggestions of the heavenly

The balanced composition is anchored by an equilateral triangle formed by Christ’s body. He sits below an arching pediment that if completed, traces a circle. These ideal geometric forms refer to the renaissance interest in Neo-Platonism (an element of the humanist revival that reconciles aspects of Greek philosophy with Christian theology). In his allegory, “The Cave,” the Ancient Greek philosopher Plato emphasized the imperfection of the earthly realm. Geometry, used by the Greeks to express heavenly perfection, has been used by Leonardo to celebrate Christ as the embodiment of heaven on earth.

Leonardo rendered a verdant landscape beyond the windows. Often interpreted as paradise, it has been suggested that this heavenly sanctuary can only be reached through Christ.

The twelve apostles are arranged as four groups of three and there are also three windows. The number three is often a reference to the Holy Trinity in Catholic art. In contrast, the number four is important in the classical tradition (e.g. Plato’s four virtues).

The Last Supper in the Early Renaissance

Andrea del Castagno’s Last Supper (1447) is typical of the Early Renaissance. The use of linear perspective in combination with ornate forms such as the sphinxes on the ends of the bench and the marble paneling tend to detract from the spirituality of the event. In contrast, Leonardo simplified the architecture, eliminating unnecessary and distracting details so that the architecture can instead amplify the spirituality. The window and arching pediment even suggest a halo. By crowding all of the figures together, Leonardo uses the table as a barrier to separate the spiritual realm from the viewer’s earthly world. Paradoxically, Leonardo’s emphasis on spirituality results in a painting that is more naturalistic than Castagno’s.

Condition

The Last Supper is in terrible condition. Soon after the painting was completed on February 9, 1498 it began to deteriorate. By the second half of the sixteenth century Giovan Paulo Lomazzo stated that, “…the painting is all ruined.” Over the past five hundred years the painting’s condition has been seriously compromised by its location, the materials and techniques used, humidity, dust, and poor restoration efforts. Modern problems have included a bomb that hit the monastery destroying a large section of the refectory on August 16, 1943, severe air pollution in postwar Milan, and finally, the effects of crowding tourists.

Because Leonardo sought a greater detail and luminosity than could be achieved with traditional fresco, he covered the wall with a double layer of dried plaster. Then, borrowing from panel painting, he added an undercoat of lead white to enhance the brightness of the oil and tempera that was applied on top. This experimental technique allowed for chromatic brilliance and extraordinary precision but because the painting is on a thin exterior wall, the effects of humidity were felt more keenly, and the paint failed to properly adhere to the wall.

There have been seven documented attempts to repair the Last Supper. The first restoration effort took place in 1726, the last and most extensive was completed in 1999. Instead of attempting to restore the image, the last conservation effort sought to arrest further deterioration and where possible, uncover Leonardo’s original painting. Begun in 1977 and comprising more than 12,000 hours of structural work and 38,000 hours of work on the painting itself, this effort has resulted in an image where approximately 42.5% of the surface is Leonardo’s work, 17.5% is lost, and the remaining 40% are the additions of previous restorers. Most of this repainting is found in the wall hangings and the ceiling.

- Copyright Statement:

All the reproduction of any forms about this work unauthorized by Singing Palette including images, texts and so on will be deemed to be violating the Copyright Laws.

To cite this webpage, please link back here.

- >> English Comments

- >> Chinese Comments

- >> French Comments

- >> German Comments

- >>Report

- Leda 1508

- Portrait of a musician

- The Virgin of the Rocks 1491

- Madonna and Child with Flowers (Benois Madonna)

- The Annunciation

- Madonna and Child with a Pomegranate

- Portrait of Ginevra Benci

- La belle Ferroniere

- Baptism of Christ

- St John the Baptist

- St John in the Wilderness (Bacchus)

- Madonna Litta

- Leda 1530

- The Virgin and Child with St Anne

- Madonna with the Yarnwinder 1501

- Madonna with the Yarnwinder after 1510

- Saint Jerome

- Leda 1510

- Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani (Lady with an Ermine)

- Leda and the Swan 1505

- The Madonna of the Carnation

- Mona Lisa

- Vitruvian Man

- Design for St Anne

- Study of a womans head

- Allegory with wolf and eagle

- Battle of Anghiari Tavola Doria

- Study of a rider

- Study for the Last Supper Judas

- Rearing horse

- Study sheet with horses and dragons

- Madonna and Child with St Anne and the Young St John detail1

- Studies of human skull

- Study for Madonna and Child with St Anne Drapery over the legs

- Study of hands

- Anatomical studies of the shoulder

- Star of Bethlehem and other plants

- Battle of Anghiari

- Drawing of the Torso and the Arms

- Adoration of the Magi

- Study of St Anne Mary and the Christ Child

- Ceiling decoration

- Study of horses

- Studies of Leda and a horse

- Womans Head

- Study for the Last Supper

- The Last Supper

- Landscape drawing for Santa Maria della Neve on 5th August 1473

Singing Palette

Singing Palette