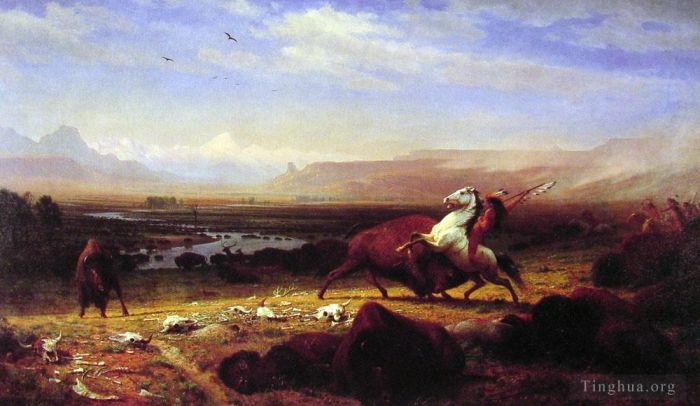

The Last of the Buffalo

Albert Bierstadt

- Price: Price on Request

- Art Type: Oil Painting

- Size:

- English Comments: 0

- International Comments: 0

- Creating Date:

- Introduction and Works of Albert Bierstadt >>

Keywords:

Buffalo

Work Overview

- The Last of the Buffalo

Albert Bierstadt

Date: 1888

Style: Luminism

Genre: genre painting

oil on canvas

overall: 180.3 × 301.63 cm (71 × 118 3/4 in.)

The Last of the Buffalo is Albert Bierstadt's final, great, western painting. Measuring six by ten feet, it mirrors in size his first massive oil, Lake Lucerne (1858), also in the National Gallery of Art collection. The ambitious landscape combines a variety of elements he had sketched during multiple western excursions. Because of its composite nature, the view incorporates many topographical features representative of the Great Plains: the dead and injured buffalo in the foreground occupy a dry, golden meadow; their counterparts cross a wide river in the middle ground; and others graze as far as the eye can see as the landscape turns to prairies, hills, mesas, and snowcapped peaks. Likewise, the fertile landscape nurtures a profusion of plains wildlife, including elk, antelope, fox, rabbits, and even a prairie dog at lower left.

Many of these animals turn to look at the focal group of a man on horseback locked in combat with a charging buffalo. In contrast with his careful record of flora and fauna, the artist's rendering of this confrontation and its backdrop of seemingly limitless herds is a romantic invention rather than an accurate depiction of life on the frontier. By the time Bierstadt painted this canvas, the buffalo was on the verge of extinction. The animals had been reduced in population to only about 1,000 from 30 million at the beginning of the century. Scattering buffalo skulls and other bones around the deadly battle, Bierstadt created what one scholar described as "a masterfully conceived fiction that addressed contemporary issues" - one that references, even laments, the destruction wrought by encroaching settlement. However, at about this time, efforts to preserve the buffalo began to garner support. In 1886, when Smithsonian Institution taxidermist William T. Hornaday traveled west, he was so distraught by the decimation of the buffalo that he became a preservationist. He returned to Washington with specimens for the Smithsonian and also with live buffalo for the National Zoo, which he helped establish in 1889 - one year after Bierstadt completed this painting.

Albert Bierstadt’s painting The Last of the Buffalo gives us a glimpse into the past. During the last half of the nineteenth century, herds of bison that once reached into the millions were nearly exterminated. Bierstadt witnessed these occurrences and, in 1888, painted an allegorical scene to reflect this. In the foreground, thousands of bison roam the plains, symbolizing the past, while the bones of dead bison reflect Bierstadt’s present. Look even closer and notice a fallen Native American, perhaps conveying a message about the plight of Plains Indians at the time.

Bierstadt shows us how the American West changed during his lifetime. The artist was aware of the end of an era in American history, and through this painting, makes his audience think. In a way, the demise of bison herds influenced how the American West was formed and is viewed today.

In 1888, Albert Bierstadt painted The Last of the Buffalo and submitted it to the organizing committee of the Paris Universal Exposition of 1889. The painting was rejected as not in line with modern art. Today it hangs in the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

The Washington Post tried to explain the rejection as Bierstadt’s fault by submitting too late and ran the headline “The Bierstadt Picture: It Was Not Rejected by the Art Loan Exhibition Committee,” on April 1, 1889:

The following extract is from yesterday’s New York World. It is headed “Real American Art:” What manner of “pigmies’” of pigment are these alleged artists who are seeking a notoriety beyond the reach of their daubs by forming ‘committees’ from their petty little selves and then giving wide publication to the fact that they have ‘rejected’ one of Albert Bierstadt’s pictures: the latest bit of this idiotic impertinence was the exclusion from a Loan Exhibition in Washington of a fine canvas which had not been loaned, but actually given, most generously, by Mr. Bierstadt for the benefit of the charity for which the exhibition was held. The only excuse for this amassing impudence furnished by the ‘artists’ in charge was the Mr. Bierstadt “did not belong to their school of art.” This same thin excuse was also given by the learned committee of chromo-tinkers who selected their own nightmares for the Paris Exhibition, insulted Mr. Inness and ‘rejected’ Mr. Bierstadt’s magnificent work, “The Last of the Buffalo.”

- Copyright Statement:

All the reproduction of any forms about this work unauthorized by Singing Palette including images, texts and so on will be deemed to be violating the Copyright Laws.

To cite this webpage, please link back here.

- >> English Comments

- >> Chinese Comments

- >> French Comments

- >> German Comments

- >>Report

- Beach at Nassau

- Tropical Landscape

- Bay of Monterey

- Sunset in the Rockies

- Westphalia

- The Wave luminism seascape

- Wind River Country

- Landscape New Hampshire

- Sunlight and Shadow

- Western Kansas

- A View from Sacramento

- The Plains Near Fort Laramie

- Pugest Sount on the Pacific Coast

- Sunrise over Forest and Grove

- Fishing Boats at Capri

- Cathedral Rock

- The Grand Tetons

- Deer Grazing Grand Tetons Wyoming

- Seaweed Harvesting

- California Sunset

- Wharf Scene

- Landscape with Cattle

- Men in Two Canoes

- Evening on the Prarie

- Fishing from a Canoe luminism seascape

- Rocky Mountain Goats

- Bernese Alps as Seen near Kusmach

- Sunset in the Yosemite Valley

- Butterfly luminism

- Mountainous Landscape

- Indian Encampment

- Lake in the Rockies

- Sunrise On The Matterhorn

- On the Saco

- Rocky Mountain

- Snow Capped Moutain at Twilight luminism seascape

- Harbor Scene

- Sunset over the River

- Seal Rock California

- California Coast

- Bernese Alps

- The Last of the Buffalo

- Sailboats on the Hudson at Irvington

- Merced River Yosemite valley

- Deer in a Landscape

- The Fallen Tree

- Bridal Veil Falls

- Western Trail the Rockies

- Sunset of the Prairies

- Tropical Landscape with Fishing Boats in Bay

- Wooded Landscape

- Conway Valley New Hampshire

- Moat Mountain Intervale New Hampshire

- Conway Meadows New Hampshire

- Italian Lake Scene

- Sunset Deer and River

- Cholooke

- The Landing of Columbus

- Seascape luminism seascape

- Nebraska Wasatch Mountains

- Boats Ashore At Sunset luminism

- Looking Down YosemiteValley

- Florida Scene

- Island of New Providence

- The Matterhorn

- Lake Lucerne

- Pikes Peak

- An Indian Encampment

- In the Foothills

- Moonlit Landscape

- Evening Glow Lake Louise

- Bears in the Wilderness

- The Oregon Trail

- Falls of Niagara from Below

- View of the Hudson

- Sunset on the Coast

- View of Donner Lake

- Nevada Falls

- Kerns River Valley California

- Sierra Nevada Mountains

- Landscape Study Yosemite California

- The Grand Tetons Wyoming

- Evening Owens Lake California

- The Domes of the Yosemite

- Grizzly Bears

- View of the Grindelwald

- Mountain Resort

- Forest Stream

- Newbraska Wasatch Mountains

- Nassau Harbor After 187luminism seascape

- Rocca de Secca

- Street in Nassau

- Canoes

- The Rocky Mountains

- Mountain Mist

- Four Rainbows over Niagara Falls

- Among the Bernese Alps

- Autumn Landscape The Catskills

- Sacramento River Valley

- Gosnold at Cuttyhunk

- Ferns and Rocks on an Embankment

- Oregon Trail

- The Arch of Octavius luminism

- On the Plains

- Passing Storm over the Sierra Nevada

- The Morteratsch Glacier Upper Engadine Valley Pontresina

- Capri

- The Golden Gate

- Sunset in California Yosemite

- Sunlight and Shadow Study

- The Emerald Pool

- Coastal View Newport

- Storm Among the Alps

- The Fishing Fleet luminism

- Tyrolean Lansscape

- Salmon Fishing on the Cascapediac River

- A Rustic Mill

- Bavarian Landscape

- Farralon Islands California luminism seascape

- Old Faithful

- Indians Fishing

- Scene in the Sierra Nevada

- The Old Mill

- Call of the Wild

- Days Beginning

- The Bombardment of Fort Sumter

- Campfire Yosemite Valley

- Indian Encampment Late Afternoon

- Indians Traveling near Fort Laramie

- In the Mountains

- View of the Grunewald

- Hatch Hatchy Valley Califrnia

- By a Mountain Lake

- Approaching Thunderstorm on the Hudson River luminism

- Among the Sierra Nevada Mountains

- Mount Washington

- View of Chimney Rock Ogalillalh Sioux Village in Foreground

- Sea Cove

- California Spring

- In Western Mountains

- Seal Rock luminism seascape

- Donner Lake from the Summit

- A View in the Bahamas

- Cathedral Rocks A Yosemite View

- Cows Watering in a Landscape

- Autumn in America Oneida County New York

- Bahama Cove

- Niagra

- Staubbach Falls Near Lauterbrunnen Switzerland

- Landscape Rockland County California

- Study forGosnold at Cuttyhunk 1602

- Nebraska On the Plains

- Mountain Scene

- Elk

- Sunset on the Mountain

- Hill and Dale

- The Portico of Octavia luminism

- North Fork of the Platte Nebraska

- Indian Camp

- Estes Park Colorado

- Sunset over a Mountain Lake

- Indian Fisherman luminism seascape

- The Ambush

- Sailing on the Hudson

- In the Foothills of the Mountais

- Landscape

- Buffalo Trail

- Surveyors Wagon in the Rockies

- Mountain Lake

- The Marina Piccola

- Figures in a Hudson River Landscape

- The Buffalo Trail

- Butterfly vluminism

- Yosemite Valley Yellowstone Park

- The Wolf River

- Indian Summer Hudson River

- Valley in Kings Canyon

- The Wetterhorn

- Liberty Cam Yosemite

- Lake Mary California

- Yosemite Valley Twin Peaks

- Deer at Sunset

- Rocky Mountains

- Sierra Nevada aka From the Head of the Carson River

- Guerrilla Warfare

- Kings River Canyon California

- Rhone Valley

- Lower Yellowstone Falls

- Lower Yosemite Valley

- On the Lake luminism seascape

- Yosemite Valley California

- Lake Louise

- Sunset

- The Sierras near Lake Tahoe

- Sunrise at Glacier Station

- Forest Sunrise

- Beach Scene

- Rainbow over a Fallen Stag luminism

- Wind River Mountains

- Wreck of the Ancon in Loring Bay luminism seascape

- Study Of A Tree luminism

- Snow Capped Moutain

- Buffalo Country

- Mariposa Indian Encampment Yosemite Valley California

- Mount Hood

- Landscape With Deer

- The Rocky Mountains Landers Peak

- Indian Encampment Shoshone Village

- Westphalian Landscape

- Storm in the Rocky Mountains

- White Mountains

- Western Landscape

- Native of the Woods luminism

- Nevada Falls Yosemite

- Mountain Landscape

- The Shore of the TurquoiseSea luminism seascape

- The Campfire

- Autumn Woods

- Campfire Site Yosemite

- Yosemite Valley

- Canadian Rockies Asulkan Glacier

- Moose HuntersCamp

- Indian Scout

- Study for Yosemite Valley Glacier Point Trail

- Seals on the Rocks Farallon Islands luminism seascape

- Pioneers of the Woods

- Lake Tahoe Spearing Fish by Torchlight

- The Sierra Nevadas

- Thunderstorn in the Rocky Mountains

- Landscape Hill and Dale

- The Great Trees

- Splendour of the Grand Tetons

Singing Palette

Singing Palette