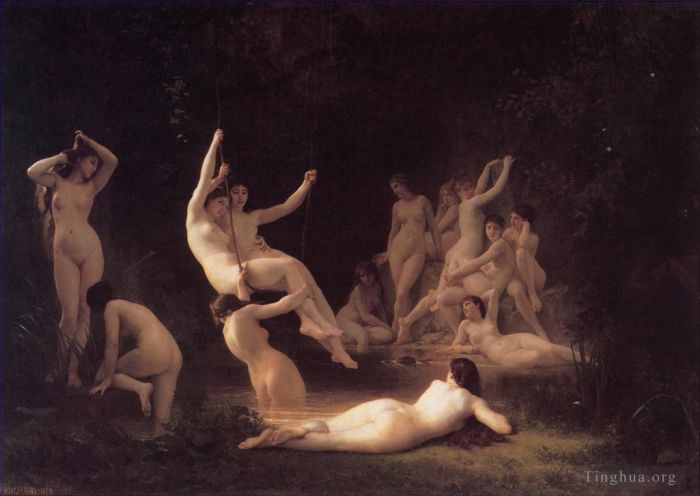

The Nymphaeum

William-Adolphe Bouguereau

- Price: Price on Request

- Art Type: Oil Painting

- Size:

- English Comments: 0

- International Comments: 0

- Creating Date:

- Introduction and Works of William-Adolphe Bouguereau >>

Keywords:

Nymphaeum

Work Overview

- The Nymphaeum

William-Adolphe Bouguereau

Original Title: La nymphee

Date: 1878

Style: Neoclassicism

Genre: mythological painting

Media: oil, canvas

Dimensions: 209.55 x 144.78 cm

Location: Haggin Museum, Stockton, CA, US

According to a writer for the Chicago Evening Post in the 1920s, Bouguereau's reputation in America was built upon his paintings of nudes. When Bouguereau's 1884 painting The Bathers (Chicago Art Institute) came up for bid at a sale of 1886, it received applause and was promptly bought for a New York saloon for eighteen thousand dollars. Critics may have quibbed over whether his nudes were erotic or chaste, but clearly the public adored them.

The Nymphaeum was created as an exhibition piece, like many of the artist's most important works. Displayed at the 1878 Universal Exposition in Paris, its complex composition, with no fewer than fifteen figures, was meant to prove Bouguereau's superiority as an established master. By exhibiting it alongside his religious, allegorical, genre, and portrait paintings (twelve in all), he demonstrated his versatility and won a medal of honor.

The subject of thirteen stark-naked nymphs cavorting in a secret woodland grotto, with a satyr and Greek youth peeping through the bushes, is, of course, pure fantasy, meant to transport the viewer from the day-to-day cares and boredom of modern urban life into a serene daydream of classical Arcadia, where there swell not flesh-and-blood women, but visions of perfection. Their impossibly smooth skins, their harmoniously proportioned bodies, their liquid movements, establish a kinship with classical sculpture and the paintings of Titian and Poussin.

While such paintings usually are considered to be out of the mainstream of modern art, Bouguereau's classical fantasies evoke interesting connections with the poetry of the Parnassian Heredia and the Symbolist Mallarme. The lines of the latter's famous "Afternoon of a Faun" (1876, 1877) closely parallel The Nymphaeum:

These nymphs, I would make them endure.

Their delicate flesh-tint so clear,

it hovers yet upon the air

heavy with foliage of sleep.

For both painter and poet, nymphs represent impossible objects of desire, as inaccessible as the Ideal itself, which both nevertheless sought in preference to mundane reality. This, it is perfectly understandable that Bouguereau's women are cloes of the same vision. The artist's refusal to be true to life irked critics and artists of the naturalist cause as much as did his perfectionist technique, which to them implied that finish was the painter's sole objective. Yet this is surely not the case, for expression and formal arrangement were equally important to Bouguereau. He distrusted the spontaneity of the Impressionists, preferring the tried-and-true methods of the old masters. After making thumbnail sketches, in which he formulated the great lines that control his compositions with graceful and logical transitions, he worked out the pattern of light and dark and the color harmonies in oil studies. Then he posed a live model in order to make figure drawings and oil sketches of heads and hands. Next came a full-scale cartoon in which he adjusted his composition and the arrangement of lights and darks. As last, ready to begin the final painting on canvas, so carefully thought out in advance, he proceeded rather rapidly. In The Nymphaeum his brush seems to caress the nudes, following contours, giving volume through subtle modelings. This painting abounds in demonstrations of the artist's virtuosity. Bouguereau's skill in painting hands and feet, troublesome details for some artists, was widely recognized and is evident here. He doe not gloss over their complex structures and, moreover, varies positions. Each nude is posed differently-several are tributes to artists he admired, Raphael, Michelangelo, Titian, Ingres- displaying front, side, and back in a variety of foreshortened views. In lighting, too, Bouguereau was a master of his craft. Figures emerge from and sink into shadows, giving both depth and variety. The rippling contour of the arm and back of the foremost nymph in the rope swing stands out forcefully, yet not sharply, against the deep shadows of the grotto, while her companion is delicately modeled by halftones. The stretching nymph on the left is bakelite so that the edges of her long hair glow like a halo.

Critics denounced Bouguereau's artifice, yet this is precisely what forges a link between the grand manner of the past and the formalism of the twentieth century. Erase the shadows, delineate the sweeping arabesques, intensify the colors, and The Nymphaeum could almost become the counterpart of similar nude idylls by Bouguereau's rebellious student Henri Matisse (1869-1954). Both artists found in surface pattern the secret of compositional harmony, which is seen here in the graceful arrangement of figures, which leads the eye from one to another. The attention to contours and grand lines creates voids with shapes nearly as interesting as solids, another connecting point between Bouguereau and Matisse.

If Bouguereau is not now usually regarded in this way, it is perhaps because his women evoke memories of silent-film starlets and because of Impressionism's rough, impastoed surfaces soon made his careful shadings and finish seem insincere. But now that it is being judged according to a standard of preference rather than truth, Bouguereau's work is again appreciated for its unique qualities.

- Copyright Statement:

All the reproduction of any forms about this work unauthorized by Singing Palette including images, texts and so on will be deemed to be violating the Copyright Laws.

To cite this webpage, please link back here.

- >> English Comments

- >> Chinese Comments

- >> French Comments

- >> German Comments

- >>Report

- Litalienne au tambourin

- Compassion

- Far Niente

- The Return of Spring

- The chilly

- Cupid and Psyche

- Jeune fille allant a la fontaine

- FemmeAuCoquillage 1885

- Jeune italienne puisant de leau

- The Madonna of the Lilies

- The Dance

- Le Baiser 1863

- The Shepherdess

- Reverie

- Girl with bouquet

- Homere et son guide

- The Prisoner

- After the Bath

- Le repos

- Tricoteuse 1879

- Charity

- Jeune ouvriere

- LAmour et Psyche enfants

- Parure des champs

- The Broken Pitcher

- Lady with Glove 1870

- Seated Nude

- Femme Blonde profil 1898

- La tricoteuse

- Adolphe Juene Fille Et Enfant MiCorps

- Portrait de lartiste

- Lidylle

- A Portrait of Leonie

- Idylle 1851

- Etude dune femme pour Offrande a lAmour

- Jeunes bohemiennes

- Le secret

- Le Jeune Bergere 1897

- Soul Carried to Heaven

- Sur la greve

- Temptation 1880

- Maternal Admiration

- The First Mourning

- Le jeune frere 1900

- Unfinished detail

- Sainte Famille

- NotreDame Des Anges

- The Nut Gatherers

- After the Bath

- Madame la Comtesse de Cambaceres

- Madone assise

- Evening Mood (Twilight or Dusk)

- Gabrielle Cot 1890

- Portrait of a Young Girl

- The Birth of Venus

- Cupid with Butterfly

- Work Interrupted

- Une Vocation

- Bohemienne au Tambour de Basque

- Jeune Fille et Enfant

- Etude tete de petite fille tete de petite fille

- Loin du pays

- La Vierge LEnfant Jesus et Saint Jean Baptiste2

- The Mischievous One

- Inspiration

- Le Lever

- Fileuse

- Faneuse

- Washerwomen of Fouesnant 1869

- Paquerettes

- Les Oreades 1902

- Psyche

- Young Woman Contemplating Two Embracing Children

- Boucles DOreilles The earrings 1891

- The Return from the Harvest

- Etude Femme Blondede face 1898

- Study for Vierge aux anges

- TheBather 1879

- Jeunesse Realism angel

- The Virgin with Angels (The Queen of the angels)

- La grappe de raisin

- Marguerite

- La brie du printemps

- La Soupe

- Berceuse

- Brother and Sister

- Au bord du ruisseau

- Psyche et LAmour

- The Nymphaeum

- Vierge consolatrice

- Baigneuse 1870

- Une vocation 1896

- The Youth of Bacchus

- Petite bergere

- A Portrait of Eugene

- Lart et la litterature

- Le Passage du gue

- Un moment repos

- The Heart’s Awakening

- La Charite 1859

- The Madonna of the Roses

- The Young Shepherdess

- Calinerie

- The Storm

- La bourrique oil on canvas

- Branche de laurier

- Le jour (Day)

- La reverence

- Mailice

- Lady Maxwell 1890

- Little beggars

- Avant le bain

- Jeune bergere 1868

- La vague

- Adolphe MAUVAISE ECOLIERE

- La priere

- Le gouter

- Pieta 1876

- Will8iam Dante et Virgile au Enfers

- The Goose Girl 1891

- Linnocence

- La Vierge LEnfant Jesus et Saint Jean Baptiste

- Beaute Romane 1904

- Loves Resistance 1885

- Moissoneuse

- The Motherland (Alma Parens)

- Reve de printemps

- A Portrait of Amelina Dufaud

- Unknown

- The Bohemian

- Portrait of a young girl 1896

- Irene

- Meditation

- The Assault

- Priestess

- La soeur ainee

- Day 1881

- The Shell

- La Vierge a Lagneau

- Bergere

- Orestes Pursued by the Furies

- Tobias Saying Goodbye to his Father 1860

- La lecon difficile

- Douleur damour

- Frere et Soeur

- Le jeune frere

- Bergere 1886

- Laurore

- Le retour du marche

- Petite boudeuse

- Song of the Angels (Virgin of the Angels)

- En penitence

- Le Crab

- La Petite Mendiante

- La soif

- The Shepherdess 1873

- The Invasion

- Petites maraudeuses

- Girl Holding Lemons 1899

- Zenobia Found by Shepherds

- Portrait Of Genevieve Celine Eldest Dau

- Flight of Love

- La Charite Romaine

- Portrait de Mlle Brissac

- Les pommes

- La palme

- Nymphs and Satyr

- Reflexion

- Flagellation of Our Lord Jesus Christ

- Wet Cupid

- The Abduction of Psyche

- The Bathers (The Two Bathers)

- Le jour des morts

- Ladmiration

- Les Jeunes Baigneuses

- Child Braiding A Crown

- Slumber

- The Little Marauder 1900

- The Pastoral Recreation 1868

- Mignon Pensive

- Unknown1

- The Knitting Girl

- Yvonne

- Meditation 1885

- Frere et soeur bretons

- Unfinished

- Biblis

- Portrait Of Madame Olry Roederer

- A Childhood Idyll

- La Gue

- Fardeau agreable

- La jeunesse de Bacchus centre dt

- The Thank Offering

- Jeune fille se defendant contre lamour

- Etude Tete de Jeune fille

- Retour des champs

- Lost Pleiad

- Les prunes

- Portrait de Mademoiselle Elizabeth Gardner

- Amour a laffut angel

- Harvester (The Grape Picker)

- La Comtesse de Montholon

- A la fontaine

- Portrait of a Young Girl Crocheting

- A Portrait of Genevieve

- La couturiere

- Femme de Cervara et Son Enfant 1861

- Modestie

- Deux soeurs

- Drawing of a Woman

- Night

- Mars

- Laurore Realism WilliamAdolphe

- Flagellation of Christ study in pencil

- Study of a Seated Veiled Female Figure

Singing Palette

Singing Palette