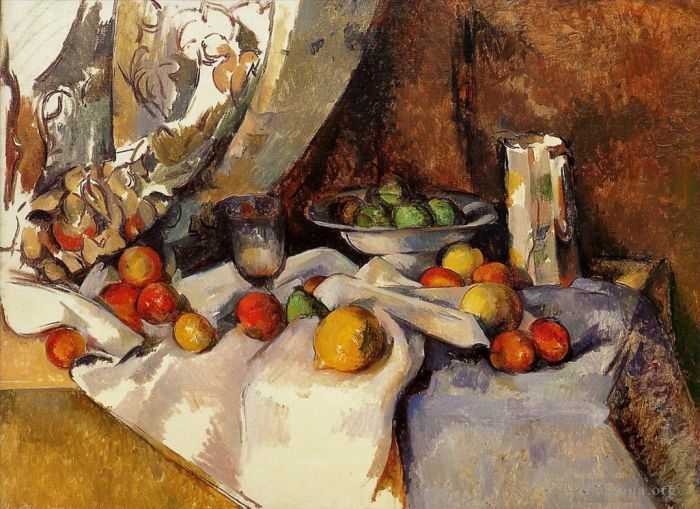

Still Life with Apples

Paul Cezanne

- Price: Price on Request

- Art Type: Oil Painting

- Size:

- English Comments: 0

- International Comments: 0

- Creating Date:

- Introduction and Works of Paul Cezanne >>

Work Overview

- Still Life with Apples

Paul Cézanne

1898

Oil on canvas

27 x 36 1/2" (68.6 x 92.7 cm)

With Still Life with Apples, Cézanne demonstrates that still life—considered the lowliest genre of its day—could be a vehicle for faithfully representing the appearance of light and space. “Painting from nature is not copying the object,” he wrote, “it is realizing one’s sensations.”

Cézanne consistently draws attention to the quality of the paint and canvas—never aiming for illusion. For example, the edges of the fruit in the bowl are undefined and appear to shift. Rules of perspective, too, are broken; the right corner of the table tilts forward, and is not aligned with the left side. Some areas of canvas are left bare, and others, like the drape of the tablecloth, appear unfinished. Still Life with Apples is more than an imitation of life—it is an exploration of seeing and the very nature of painting.

Cézanne was fascinated by optics and tried to reduce naturally occurring forms to their geometric essentials—the cone, the cube, the sphere. He used layers of color on these shapes to build up surfaces, outlining the forms for emphasis. His deep study of geometry in painting led him to become a master in perspective. Until the end of his life, Cézanne received little public success and was repeatedly rejected by the Paris Salon. In his last years, and particularly after his death, his work began to influence many younger artists, including Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

Still Life with Apples demonstrates that the genre of still life can be a vehicle for faithfully representing not only objects but also the appearance of light and space. Painting from nature is not copying the object, Cézanne wrote, it is realizing ones sensations. He consistently drew attention to the quality of the paint and canvasnever aiming for illusion. For example, the edges of the fruit in the bowl are undefined and appear to shift. Rules of perspective, too, are broken; the right corner of the table tilts forward and is not aligned with the left side. Some areas of canvas are left bare, and others, like the drape of the tablecloth, appear unfinished. Still Life with Apples is more than an imitation of lifeit is an exploration of seeing and the very nature of painting.

Throughout his life, the French painter Paul Cézanne returned again and again to the still life. Encompassing small—scale domestic scenes rather than grand public ones, still life was considered the lowliest of genres by the French Royal Academy, the official arbiter of great art in the nineteenth century. Yet in Still Life with Apples, Cézanne proved that this modest genre could be a vehicle for thinking through the Impressionist project of faithfully representing the appearance of light and space. "Painting from nature is not copying the object," he wrote, "it is realizing one's sensations."

Cézanne consistently draws our attention to the quality of the paint and canvas, and we never lose ourselves in illusion. For example, the edges of the fruit in the bowl are hard to define, appearing to shift before our eyes. Cézanne's scene defies the rules of linear perspective (a system for creating the illusion of space on a flat surface, wherein every object is seen from a single, fixed point of view) and instead gives us shifting views. The right corner of the table tilts forward, and fails to align with the left side; the pitcher, the bowl, and the glass all tilt to the left, as if magnetically drawn to the curtain. Even though the artist worked on this painting for a number of years, some areas of canvas are left bare, and others, like the drape of the tablecloth on the right edge of the table, appear unfinished. Still Life with Apples is more than an imitation of life—it is an exploration of seeing and the very nature of painting.

- Copyright Statement:

All the reproduction of any forms about this work unauthorized by Singing Palette including images, texts and so on will be deemed to be violating the Copyright Laws.

To cite this webpage, please link back here.

- >> English Comments

- >> Chinese Comments

- >> French Comments

- >> German Comments

- >>Report

- Still Life with Flowers and Fruit

- View of Auvers

- Couple in a Garden

- Ile de France Landscape

- The Turn in the Road at Auvers

- Orchard

- Madame Cezanne Leaning on a Table

- Chestnut Tree and Farm

- The Chateau de Medan

- The Eternal Woman 2

- The Obstpfluckerin

- Still Life with Apples and a Glass of Wine

- Mont Sainte-Victoire

- The Hanged Man House in Auvers

- Morning in Provence

- Mont Sainte-Victoire

- Compotier and Plate of Biscuits

- The Card Players 1892

- Still life with Apples

- Still Life with Oranges

- Bathers 1894

- Montagne Sainte Victoire and the Black Chateau

- Sea at L Estaque

- Still Life with Plaster Cupid 2

- Chrysanthemums

- The Black Marble Clock

- The Four Seasons Autumn

- Houses in Provence near Gardanne

- Pine and Aqueduct

- Mont Sainte-Victoire

- Forest near the rocky caves above the Chateau Noir

- Still life with skull candle and book

- Large Trees at Jas de Bouffan

- Peasant

- Plain by Mont Sainte-Victoire

- Still life in front of a chest of drawers

- View of L Estaque 2

- The Seine at Bercy

- Bathers 1880

- The Bay of L Estaque from the East

- Poplars

- Apples on a Sheet

- Still life with basket

- Girl at the Piano

- Preparation for the Funeral

- Four Bathers 188

- Mountains in Provence L Estaque

- View of Bonnieres

- Farm in Normandy Summer

- Gardanne

- Bathers

- Bathers and Fisherman with a Line

- Bridge and Waterfall at Pontoise

- The Railway Cutting

- Young Girl with a Doll

- The Robbers and the Donkey

- Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from les Lauves

- The Gulf of Marseille Seen from LEstaque

- Flowers in a Vase 2

- Houses Along a Road

- Sugarbowl Pears and Tablecloth

- Study of Bathers

- Still Life with Sugar

- Still life with fruit geraniums Stock

- Chateau Noir

- Harlequin

- The House with Cracked Walls

- A Lunch on the Grass

- Still life with jug

- Large Bathers

- Legendary Scene

- The Temptation of St Anthony

- Apples and Biscuits

- The Pool at Jas de Bouffan

- In the Woods

- Still Life Vase with Flowers

- Dish of Apples

- Village in the Provence

- Bibemus Quarry

- L Estaque View Through The Pines

- Bathers at Rest 1877

- Five Bathers

- Self Portrait with Palette

- Four Bathers 1890

- Still Life Bowl and Milk Jug

- The Gulf of Marseille Seen from LEstaque 1885

- Orchard in Pontoise

- Still Life with Red Onions

- Flowers in an Olive Jar

- House and Trees

- Corner of Quarry

- Still life with Italian earthenware jar

- Paul Alexis Reading at Zola House

- A Painter at Work

- Bathsheba

- Boy Resting

- Still life with open drawer

- Interior with Two Women and a Child

- Fruit Bowl Pitcher and Fruit

- The Judgement of Paris

- Ginger Jar

- Landscape in Provence

- Landscape Study after Nature

- The Sea at l Estaque

- House behind Trees on the Road to Tholonet

- The House and the Tree

- Bridge over the Marne

- Potted Plants

- Bathers 2

- The Barque of Dante after Delacroix

- The Pool at Jas de Bouffan

- Still Life Bread and Leg of Lamb

- Five Bathers 2

- Dahlias In A Delft Vase

- Three Bathers

- Bacchanalia The Battle of Love

- Mountains in Provence

- Castle of Marines

- In the Oise Valley

- The Alley at Chantilly 1888

- Auvers View from Nearby

- Landscape with Mill

- The Bathers

- The Abduction

- The Etang des Soeurs at Osny

- Curtain Jug and Fruit

- Still life with seven apples

- Still life bottle of rum

- The Battle of Love

- The Alley at Chantilly

- Portrait of Madame Cezanne 3

- Reflections in the Water

- Rocks near the Caves below the Chateau Noir

- Portrait of Madame Cezanne 2

- Bend in Forest Road

- The Abandoned House

- Forest

- Rocks at Fountainebleau

- Still Life Plate and Fruit 2

- The Bay of lEstaque and Saint Henri

- Table Napkin and Fruit

- Portrait of an old man

- The Feast The Banquet of Nebuchadnezzar

- Woods with Millstone

- Jourdan Cottage

- Self Portrait with Beret

- Sugar Bowl Pears and Blue Cup

- Bathers 1906

- Paul Alexis Reading a Manuscript to Emile Zola

- The House of Dr Gached in Auvers

- Lane of Chestnut Trees at the Jas de Bouffan

- L Estaque under Snow

- Tulips in a Vase

- Four Bathers

- Factories Near Mont de Cengle

- Mont Sainte-Victoire

- Still Life Apples and a Glass

- Leaving on the Water

- Still Life with Plaster Cupid

- Woman with Parrot

- Fruit and Jug on a Table

- Dessert

- Trees and houses

- Madame Cezanne in a Yellow Chair

- Boy in a Red Vest 3

- Pyramid of skulls

- Chestnut Trees and Farmstead of Jas de Bouffin

- Still Life with Fruit Dish (Compotier Glass and Apples)

- Landscape 1862

- Cottages of Auvers

- Bathers

- Mont Sainte-Victoire

- Boy in a Red Waistcoat

- Horse chestnut trees in Jas de Bouffan

- The Murder

- Forest 1890

- Bathers 1887

- Still life pitcher and fruit

- Flowers and Fruit

- Mont Sainte-Victoire

- Ile de France Landscape 2

- Bend in the River

- Still Life Skull and Waterjug

- The farm of Bellevue

- The House of Pere Lacroix in Auvers

- Self Portrait

- Bathers 1905

- Still Life with Blue Pot

- Young Man and Skull

- L Estaque View through the Trees

- Village behind Trees

- Pot of Flowers

- In the Park of Chateau Noir

- Maison Maria with a View of Chateau Noir

- Pastoral or Idyll

- Landscape with Waterline

- Madame Cezanne in the garden

- View of Auvers 2

- Still life with bottles and apples

- Still life with a fruit dish and apples

- Life in the Fields

- Flowers in a Vase

- Pierrot and Harlequin Mardi Gras

- Bibemus Quarry 1900

- Afternoon in Naples

- The Pigeon Tower At Bellevue

- Sorrow

- Still Life with Bread and Eggs

- Still life

- Satyres and Nymphs

- Still Life with Apples and Peaches

- Portrait of Madame Cezanne

- Chateau Noir 2

- The Eternal Woman

- Hortense Breast Feeding Paul

- Etude Paysage a Auvers

- The Artists Father Reading L’Événement

- Two Vases of Flowers

- Gardanne Horizontal View

- The roofs

- The Lacd Annecy

- Still Life 1877

- House with Red Roof

- Melting Snow Fontainbleau

- Still Life with Apples

- Dish of Peaches

- Still Life Tulips and apples

- Apples Pears and Grapes

- Still Life with Pomegranate and Pears

- Still Life with a Curtain

- Still Life with Soup Tureen 1884

- Fisherman on the Rocks

- In the Forest

- House and Farm at Jas de Bouffan

- Riverbanks

- Still Life with Green Pot and Pewter Jug

- Basket of Apples

- Landscape

- Rocks at L Estaque

- Road near Mont Sainte Victoire

- Don Quixote View from the Back

- Bathers 1875

- The Blue Vase

- View of L Estaque and Chateaux d If

- Bather from the Back

- Bathers in front of a tend

- Tall Trees at the Jas de Bouffan

- The pond of the Jas de Bouffan

- Chateau Noir 3

- Landscape 1867

- Road

- Mount Sainte Victoire Seen from Gardanne

- Road Trees and Lake

- The Buffet

- Still Life Flowers in a Vase

- View of L Estaque

- Still Life with a Ginger Jar and Eggplants

- Four Bathers 2

- The Card Players

- Chestnut Trees at the Jas de Bouffan

- The Banks of the Marne

- Road 1871

- The Alley at Chantilly 2

- Still Life with a Chest of Drawers 1887

- The Mont Sainte-Victoire and the Viaduct of the Arc River Valley

- Bottom of the Ravine

- Still Life Apples and Pears

- Young Italian Girl Resting on Her Elbow

- Leda and the Swan

- The Temptation of St Anthony 2

- Apples

- The Three Skulls

- The Four Seasons Spring

- Cote du Galet at Pontoise

- Houses at the LEstaque

- Still Life with Apples 1894

- Mont Sainte-Victoire

- The Aqueduct and Lock

- Promenade

- Montagne Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine

- Gardanne 2

- Apples and Oranges

- The Card Players

- Bibemus Quarry 1898

- Christ in Limbo

- Still life Delft vase with flowers

- Woman in Blue Madame Cezanne

- Still life peppermint bottle

- The Halle aux Vins seen from the rue de Jussieu

- The Smoker

- Bather with Outstreched Arms

- Boy in a Red Vest 4

- Mont Sainte Victoire 6

- Still Life with a Plate of Cherries 1887

- Still life with apples and fruit bowl

- The Oilmill

- A Close

- Flower pot at a table

- Three Bathers 1882

- Moulin de la Couleuvre at Pontoise

- Millstone and Cistern Under Trees

- The Four Seasons Summer

- Mont Sainte-Victoire

- Still Life with Skull

- Bouquet of Flowers

- Apples and a Napkin

- Mont Sainte‑Victoire Seen from the Bibémus Quarry

- Mount Sainte-Victoire

- In the Woods 2

- Still life jug and fruit on a table

- A Modern Olympia

- L Estaque View through the Trees

- Montagne Sainte Victoire from Lauves

- Boy in a Red Vest

- The Lion and the Basin at Jas de Bouffan

- Vase of Flowers

- Bathers at Rest

- Jas de Bouffan the pool

- The Great Pine

- Farm at Montgeroult

- Couples Relaxing by a Pond

- River in the plain

- The Fountain

- Still Life with Pomegranate and Pears 2

- L Estaque with Red Roofs

- Bibemus Quarry 2

- The Four Seasons Winter

- The Card Players 2

- Turning Road at Montgeroult

- A Modern Olympia 2

- Jas de Bouffan

- Still Life with Apples 2

- Man Standing Arms Extended

- Road in Provence

- Houses in the Greenery

- Landscape at the Jas de Bouffin

- The valley of the Oise

- Large Pine and Red Earth

- The Bend in the road

- Jourdans Cottage

- Still Life Apples a Bottle and Chairback

- The Fountain 2

- The farm of Bellevue 2

- Large Pine

- Rose Bush

- The Rum Punch

- Still Life with Carafe

- Rocks

- Still Life with Apples a Bottle and a Milk Pot

- Seascape

- Woman Diving into Water

- Self Portrait in a Felt Hat

- Landscape at Midday

- The Trees of Jas de Bouffan in Spring

- Mont Sainte Victoire

- Pots of Geraniums

- Mont Sainte Victoire

- The Oise Valley

- Near Aix En Provence

- Chateau de Madan

- The Manor House at Jas de Bouffan

- Mont Sainte Victoire 1906

- Roofs in L Estaque

- House in Provence

- Pool and Lane of Chestnut Trees at Jas de Bouffan

Singing Palette

Singing Palette