The Roses of Heliogabalus

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema

- Price: Price on Request

- Art Type: Oil Painting

- Size:

- English Comments: 0

- International Comments: 0

- Creating Date:

- Introduction and Works of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema >>

Keywords:

Roses, Heliogabalus

Work Overview

- The Roses of Heliogabalus

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Date: 1888

Style: Romanticism

Genre: genre painting

Media: oil, canvas

Dimensions: 132.1 x 213.9 cm

Location: Private Collection

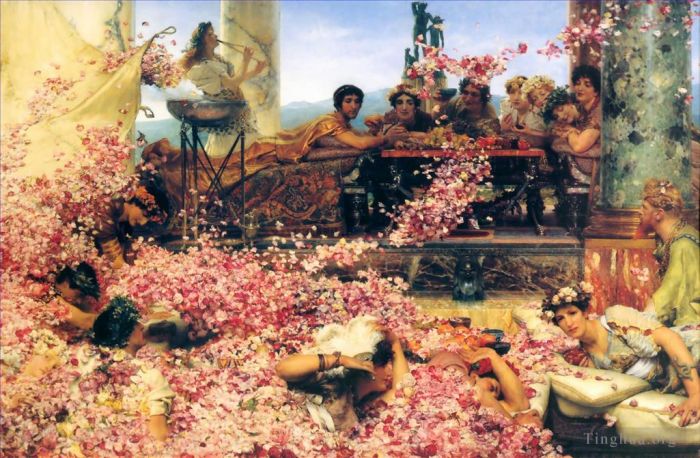

The Roses of Heliogabalus is an 1888 painting by the Anglo-Dutch artist Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema. It is currently owned by the Spanish-Mexican billionaire businessman and art collector Juan Antonio Pérez Simón.

The painting measures 132.7 × 214.4 centimetres (52.2 × 84.4 in). It shows a group of Roman diners at a banquet, being swamped by drifts of pink rose petals falling from a false ceiling above. The Roman emperor Elagabalus reclines on a platform behind them, wearing a golden robe and a tiara, watching the spectacle with other garlanded guests. A woman plays the double pipes beside a marble pillar in the background, wearing the leopard skin of a maenad, with a bronze statue of Dionysus, based on the Ludovisi Dionysus, in front of a view of distant hills.

The painting depicts a (probably invented) episode in the life of the Roman emperor Elagabalus, also known as Heliogabalus (204–222), taken from the Augustan History. Although the Latin refers to "violets and other flowers", Alma-Tadema depicts Elagabalus smothering his unsuspecting guests with rose petals released from a false ceiling. The original reference is this:

Oppressit in tricliniis versatilibus parasitos suos violis et floribus, sic ut animam aliqui efflaverint, cum erepere ad summum non possent.[4]

In a banqueting-room with a reversible ceiling he once buried his guests in violets and other flowers, so that some were actually smothered to death, being unable to crawl out to the top.[5]

In his notes to the Augustan History, Thayer notes that "Nero did this also (Suetonius, Nero, xxxi), and a similar ceiling in the house of Trimalchio is described in Petronius, Sat., lx." (Satyricon).

The painting was commissioned by Sir John Aird, 1st Baronet for £4,000 in 1888. As roses were out of season in the UK, Alma-Tadema is reputed to have had rose petals sent from the south of France each week during the four months in which it was painted.[7]

The painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy summer exhibition in 1888. Aird died in 1911, and the painting was inherited by his son Sir John Richard Aird, 2nd Baronet. After Alma-Tadema died in 1912, the painting was exhibited at a memorial exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1913, the last time it was seen at a public exhibition in the UK until 2014.[citation needed]

Alma-Tadema's reputation declined markedly in the decades after his death. Following the death of the 2nd Baronet in 1934, the painting was sold by his son, the 3rd Baronet, in 1935 for 483 guineas. It failed to sell at Christie's in 1960, and was "bought in" by the auction house for 100 guineas.

Eventually, it was acquired by Allen Funt: he was the producer of Candid Camera, and a collector of Alma-Tadema's at a time when the artist remained very unfashionable. After Funt experienced financial troubles, he sold the painting along with the rest of his collection at Sotheby's in London in November 1973, achieving a price of £28,000. The painting was sold again by American collector Frederick Koch at Christie's in London in June 1993 for £1,500,000.

-----------------------

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema's "The Roses of Heliogabalus" is one of his most famous paintings, and also a representation of one of the most well-known stories about the Roman Emperor Heliogabalus. As the second part of our feature on Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, today's post will focus on "The Roses of Heliogabalus" and the emperor himself. (If you missed it the first time around, check out Tuesday's post for details on the artist.)

1. "The Roses of Heliogabalus" depicts guests of Emperor Heliogabalus being suffocated by a shower of rose petals for the entertainment of the emperor. The original tale of the event mentions violets as the flowers of death. At the time of the painting, though, roses were symbolic of sensual beauty, corruption, and death, which may be why Tadema chose to use them.

2. For "The Roses of Heliogabalus," Tadema ordered roses from the Riviera even though it was winter. For four months, he had blossoms delivered weekly to his London studio so he could achieve the realistic look for which he became famous.

3. Heliogabalus, also known as Elagabalus, was born Varius Avitas Bassianus. He served as a priest of the god El-Gabal; at age 14, due in large part to his grandmother's finagling, he became emperor. Four years later, at the age of 18, he was assassinated, which some sources also attribute to his grandmother's finagling.

4. Despite his short life, Heliogabalus managed to marry at least 5 women, one of whom was a Vestal Virgin. He also referred to a male charioteer, Hierocles, as his "husband" and supposedly married another male athlete, Zoticus, in a public ceremony in Rome.

5. According to some accounts, Heliogabalus offered a significant sum of money to whomever could make him a woman. He was also said to have worn make-up, removed bodily hair, and worn wigs to prostitute himself, first in taverns and brothels, and then out of the imperial palace. Upon being greeted by Zoticus with, "My Lord Emperor, Hail," Heliogabalus replied, "Call me not Lord, for I am a Lady." However, the veracity of many of the claims about Heliogabalus is unknown; a black propaganda campaign had been waged against him after his death. Many stories, including the one that inspired Tadema's painting, are considered to be false or at least exaggerated.

--------------------

In historic pictures much depends on the choice of subject. In the Academy of 1888 there was a scene from Roman history by an eminent painter, Mr. Alma Tadema. It was entitled "The Roses of Elagabalus." In its own sphere and range of art, it was a picture of unquestionable power, and it was at once purchased for an immense sum of money; yet it can hardly fail to awaken very painful reflections.

Let us try to describe it.

The Roman emperor, Elagabalus, or Heliogabalus, who had been a priest of the Syrian sun-god, and was justly murdered at eighteen, was the most execrably infamous of human kwretches. At one of his feasts he had the ^wriuin, above his dining-hall, suddenly let loose, to shower tons of roses on his parasites, some of whom, it is said, were suffocated by the flowers, and drawn dead from beneath the mass.

Such is the scene painted by Mr. Alma Tadema, and with marvellous power in imitating gold, silver, marble, jewels, and human splendour, debased in the person of Elagabalus to the lowest depths of all that is earthly, and devilish. Roses, yes! a torrent of them; and what a divine thing a rose is! "If there were but one rose in all the world, and a man could make it," said Luther, "we should deify that man." In one of his finest poems, Victor Hugo, after speaking of the passion, despair, and fury which sometimes rent his heart in exile, when he thought of the tyranny and oppression which is in the world, ends the poem with the words, "I take a rose — I look at it — and I am appeased." Yes! a rose is a divine and perfumed miracle of God; it may awake in a holy soul thoughts too deep for tears. But the humblest rose that ever had the dew of morning on its pure leaves, is worth the whole avalanche of these sickening, crumpled, decaying blossoms for vile purposes vilely abused.

And Youth, which, as the poet-preacher says, "dances like a bubble nimble and gay, and shines like a dove's neck, and the colours of the rainbow, which hath no substance, but of which the very colours and image are fan- tastical," why are we asked to look on this its inexpressible degradation? Elagabalus! — there lies that shame and monstrosity of the human race, the loathly boy-emperor, on his couch of silver and mother-of-pearl, in his long golden Phoenician robe, leaning on cushions stuffed ivith the small plumes of partridges; his intriguing and hideous grandmother, Julia Mcesa, and other hard-featured women beside him; he leering over his wine-cup at the bejewelled wretches below him, while the fittest unconscious comment ,on the whole scene is the hideous head of the bronze monster, which grins like a demon, just above. An historic painting, truly! — but what history! In all the stately and noble scenes of Roman rule, its lofty figures, its heroic ideals, its magnificent magnanimities, the all but Christian grandeur of its endurance and its patriotism, was there nothing worth the infinite toil of this skilled hand but this carnival of bejewelled sensualism, this portent of abysmal depravity, this avalanche of wasted roses over the dazzling banquet of the world, the devil, and the flesh — that banquet where the dead are there, and the guests in the depths of hell.

----------------------

The Roses of Heliogabalus was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1888 and has become one of the best known images in the whole of Victorian art. The picture depicts the ultimate decadence of the Roman Emperor Heliogabalus who for his own pleasure is causing his guests to be suffocated beneath a torrent of falling rose petals released from awnings above them. This exploration of the pitfalls of excess and the proximity of pleasure and pain is rendered with great technical brilliance.

The Roses of Heliogabalus was bought by Sir John Aird, one of the great Victorian engineers who was responsible for the construction of the Aswan Dam and the removal of the Crystal Palace from Hyde Park to Sydenham. The picture was last exhibited in London in 1913 when it was included in the Alma-Tadema memorial exhibition at the Royal Academy.

The show climaxes with a roomful of late works, dominated by the extraordinary The Roses of Heliogabalus, regarded now as his signature work and showing a little known incident from late Roman history, in which an emperor smothered his dinner guests in rose petals. If Alma-Tadema the Dutch democrat naturally disapproves of this cruel excess, boy does he have fun painting it. Clouds of pink petals float over the faces of the leering emperor and his cronies, depicted with a near-photographic realism; combined with the uniform pink colour, it brings a curious, but inescapable flavour of the advertising poster or the department store window display – art-forms then just coming into their own. The faces of the guests expiring in the sea of flowers below are, of course, those of well-bred young Victorian ladies.

As British power approached its zenith, Alma-Tadema created images of the ancient empire that provided the model for Britain’s modern imperial adventure, in which the Victorians themselves played the starring roles. The touching fact behind this evocative exhibition is that we can perceive that in a way that they, and indeed he, never could.

- Copyright Statement:

All the reproduction of any forms about this work unauthorized by Singing Palette including images, texts and so on will be deemed to be violating the Copyright Laws.

To cite this webpage, please link back here.

- >> English Comments

- >> Chinese Comments

- >> French Comments

- >> German Comments

- >>Report

- Death of the Pharaohs Firstborn Son

- A Pyrrhic Dance

- Summer Offering Young Girl with Roses

- Between Venus and Bacchus

- A Roman Emperor AD41detail1

- Portrait of Ignacy Jan Paderewski

- Portrait Of Mrs Charles Wyllie

- The Massacre of the Monks of Tamond

- Pandora

- Who is it

- Egyptian juggler

- A Family Group

- The Death of Hippolytus

- A reading from homer detail

- A world of their own

- The Crossing of the River Berizina 1812

- A Hearty Welcome

- In the Temple Opus 1871

- The Flower Market

- A Roman Art Lover2

- The Sculptors Model

- Ask me no more

- In My Studio

- Expectations

- Welcome footsteps

- A Bath An Antique Custom

- A Declaration

- Portrait of a Woman

- Autumn Vintage Festival

- Ave Caesar Io Saturnalia

- Spring Flowers

- Unwelcome Confidences

- The Picture Gallery

- A Roman Emperor

- Boating

- Caracalla and Geta

- The voice of spring

- The Finding of Moses 1904

- Shy

- A votive offering

- A Harvest Festival A Dancing Bacchante at Harvest Time

- Thou Rose of all the Roses

- Portrait of Aime Jules Dalou his Wife and Daughter

- Flora Spring in the Gardens of the Villa Borghese

- The Sculpture Gallery detail

- A Collection of Pictures at the Time of Augustus

- Prose

- A Difference of Opinion

- A Silent Greeting

- Caracalla

- The Potter

- Poetry

- Confidences

- Maria Magdalena

- Golden hour

- Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon

- A Listner

- Exhausted Maenides after the Dance

- Interrupted

- The Vintage Festival

- Master John Parsons Millet

- A greek woman

- Proclaiming Claudius Emperor

- Flag Of Truce

- Between Hope and Fear

- The Drawing Room at Townshend House

- Venantius Fortunatus Reading His Poems to Radegonda VI

- Portrait Of Miss Laura Theresa Epps

- Strigils and sponges

- Always Welcome

- Drawing Room Holland Park

- Self Portrait

- Pastimes in Ancient Egyupe 300Years Ago

- The Coliseum

- The Roses of Heliogabalus

- Miss Alice Lewis

- Sunshine

- The years at the spring

- Agrippina with the ashes of Germanicus Opus XXXVII

- Interior of Caius Martiuss House

- A reading from homer

- Joseph Overseer of the Pharoahs Granaries

- Tibullus at Delias

- God Speed

- Midday Slumbers

- The Roman Wine Tasters

- Hadrian Visiting a Romano British Pottery

- A Roman Art Lover

- British 18361912A Roman Scribe Writing Dispatches

- On the Road to the Temple of Ceres

- In the Peristyle2

- Faust and Marguerite

- The Baths of Caracalla

- The parting kiss

- Sappho and Alcaeus

- Interior of the Church of San Clemente Rome

- Sculptors in Ancient Rome

- Egyptian Chess Players

- Sir Lawrence From An Absent One

- A Dedication to Bacchus

- Preparation in the Colosseum detail

- Vain Courtship

- Preparation in the Colosseum

- Mrs George Lewis and Her Daughter Elizabeth

- Dolce Far Niente

- Loves Jewelled Fetter

- A Picture Gallery

- When Flowers Return

- Courtship

- A Favourite Custom

- Maurice Sens

- The Favourite Poet

- Tarquinius Superbus

- Unconscious Rivals

- The Sculpture Gallery

- Architecture in Ancient Rome

- Hopeful

- Portrait of the Singer George Henschel

- After the audience

- Cherries

- Sir Lawrence The Soldier Of Marathon

- Hero 1898

- The Triumph of Titus

- A Prize For The Artists Corps

- Antony and Cleopatra

- Ninetyfour in the Shade

- The Education of the Children of Clovis

- The Frigidarium

- Resting

- Silver Favourites

- Entrance to a roman theatre

- Gallo Roman Women

- An exedra

- Sir Lawrence An Audience

- Loves Votaries

- Not at home

- The Siesta

- A sculpture gallery

- A Street Altar

- Pottery painting

- The Discourse

- Courtship the Proposal

- Lawrence Bacchanale 1871

- Under the Roof of Blue Ionian Weather

- Xanthe and Phaon

- Leaving Church in the Fifteenth Century

- Summer Offering

- Water Pets

- A Birth Chamber

- Portrait of Anna Alma Tadema

- In the Tepidarium

- Pleading

- The Soldier of Marathon

- This is our Corner Laurense and Anna Alma Tadema

- Whispering Noon

- Catullus at Lesbias

- The Way to the Temple

- The Honeymoon

- The Conversion Of Paula By Saint Jerome

- An earthly paradise

- Preparations for the Festivities

- Promise of spring

- Comparisons

- An Oleander

- A kiss

- The Family Group

- My Studio

- The Epps Family Screen

- In the Time of Constantine

- Lesbia Weeping over a Sparrow

Singing Palette

Singing Palette