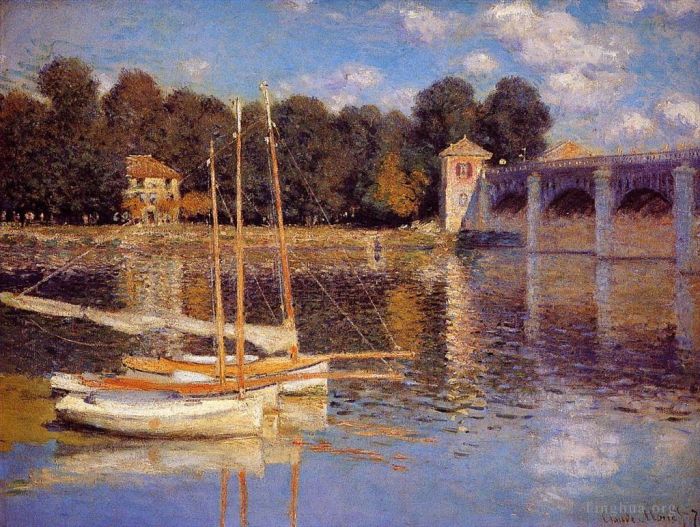

The Bridge at Argenteuil

Claude Monet

- Price: Price on Request

- Art Type: Oil Painting

- Size:

- English Comments: 0

- International Comments: 0

- Creating Date:

- Introduction and Works of Claude Monet >>

Keywords:

Bridge, Argenteuil

Work Overview

- The Bridge at Argenteuil

Claude Monet

Date: 1874

Style: Impressionism

Oil on canvas, 60 x 80 cm

Genre: cityscape

National Gallery of Art, Washington

In 1874, the year of the first Impressionist exhibition, Claude Monet painted the Argenteuil Bridge seven times, and the railway bridge which spans the Seine upstream from the village, four times. This shows how attached the artist was to the motif, using the flowing river as a counterpoint for the geometrical mass of the bridge and its piles reflected in the water.

Here the foreground is filled with sailboats at their mooring. The effects of light on the masts and on the roofs of the houses on the bank in the background are an opportunity for the play of complementary colours (orange and blue) which accentuate the glittering light. The Argenteuil Bridge exhibits great variety in treatment: the still firm outlines of the solid or structured elements, such as the sailboats and the bridge, a smooth, even texture for the water in the foreground, and choppy brushstrokes capturing the reflections in the middle ground.

Monet settled in Argenteuil in 1871, after his return from England. Apart from minor interruptions, he stayed here 1878. He was followed to Argenteuil by Renoir, Sisley, Pissarro, and Manet. The six-year period that he spent there was a prolific one; during his first year at Argenteuil alone, he produced almost as many paintings as he had during the three previous years combined. Of the many works the artist produced during this first year, Argenteuil among them, the majority depict the Seine.

Whereas Manet gained effect by sparkling accents standing out against low tones in his open-air pictures, Monet worked out the equation of light and colour more comprehensively and in more variety. In The Bridge at Argenteuil the equivalence is complete, the glow of light produced by pure and unmixed colour pervades the canvas and surrounds the forms appearing in it. The interplay between the short strokes indicative of ripples and the larger areas of colour is made with a typical flexibility of skill.

The accusation is sometimes made against the Impressionists that in their concern with atmosphere they lost sight of qualities of form and composition. Analysis of this painting would show, in spite of its apparent lack of pre-intended arrangement, how coherent it is in design. The verticals of the masts, of the houses and bridge piers and their reflections are set down firmly with an obvious sense of their pictorial value. There are those echoes of form and colour in which harmony of composition is to be found. The line of the furled sail is caught by the ribbed sky at the left; the warm tones of buildings are echoed in the details of the yachts; the dapple of clouds in the blue sky (with its deeper richness of blue in reflection) has its tonal equivalent in the reflections of the boats. To relax and look at the picture without analytic effort, however, is to see it resolve into an idyllic vision in which modern life has introduced no jarring note.

- Copyright Statement:

All the reproduction of any forms about this work unauthorized by Singing Palette including images, texts and so on will be deemed to be violating the Copyright Laws.

To cite this webpage, please link back here.

- >> English Comments

- >> Chinese Comments

- >> French Comments

- >> German Comments

- >>Report

- The Japanese Footbridge

- Apple Trees in Bloom at Giverny

- Apple Trees near Vetheuil

- The Tuleries study

- The Grand Canal

- The Water Lily Pond

- Flowering Trees near the Coastcirca

- Isleets at PortVillez

- The Seine at Vetheuil

- The Japanese Bridge VII

- Poppy Field in a Hollow near Giverny

- The Banks of the Seine at the Argenteuil Bridge

- The Ice Floes

- The Church at Varengeville Morning Effect

- Road near Giverny

- Church at Jeufosse Snowy Weather

- L Ally Point Low Tide

- The Blue Row Boat

- Chrysanthemums

- The Seine at PortVillez Harmony in Blue

- Sailboatscirca

- Lane in Normandy

- Water Lilies 1911919

- The Red House

- The Rue Montorgueil in Paris

- Late Afternoon in Vetheuil

- Le Grand Canal or The Grand Canal in Venice

- Lemons on a Branch

- Cliff near Dieppe

- Chrysanthemums

- Bordighera

- Green Reflection left half

- Port Donnant Belle Ile

- View of Amsterdam

- Boats Lying at Low Tide at Facamp

- Irises in Monet’s Garden

- Landscape on the Ile Saint-Martin

- Haystacks at Giverny 1895

- The Luncheon

- View of Vetheuil

- At Cap d Antibes Mistral Wind

- In the Norvegienne

- Rowboat on the Seine at Jeufosse

- Irises in Monets Garden at Giverny

- The Banks of the River Epte at Giverny

- The Bridge over the Water Lily Pond 1905

- Peaches

- The Path at Giverny

- The Manneport Etretat

- Le Rue de La Bavolle at Honfleur

- 4 Morning on the Seine

- Poplars

- Lilac Irises

- Windmill near Zaandam

- Water Lily Pond at Giverny

- The Coast at SainteAdresse

- In the Meadow detail

- Red Water Lilies

- Taking a Walk on the Cliffs of SainteAdresse

- Boats on the Beach Etretat

- Arm of the Seine near Giverny at sunrise

- The Water Lily Pond right side

- The Palazzo Ducale II

- The Manneport Seen from the East

- Turkeys

- River Scene at Bennecourt

- The Bend of the Seine at Lavacourt Winter

- Charing Cross Bridge Reflections on the Thames

- Lane in the Poppy Fields Ile SaintMartin

- Arm of the Seine at Giverny

- The Garden at Argenteuil aka The Dahlias

- Windmills near Zaandam

- The Seine at Port Villez Snow Effect

- The Boulevard de Pontoise at Argenteuil Snow Effect

- The Seine at Vetheuil II 1879

- The Seine and the Chaantemesle Hills

- A Row of Poplars

- Water Lilies 1914

- Barge on the Seine at Vertheuil

- Fields of Flowers and Windmills near Leiden

- Boats on the Beach at Etretat

- The Manneport at High Tide

- The Pyramids of Port Coton BelleIleenMer

- The Cliff at Varengeville

- Vase of Poppies

- Jar of Peaches

- Poplars on the Banks of the Epte

- Morning left detail

- The Road to Vetheuil

- The Beach at Sainte Adresse

- Grove of Olive Trees in Bordighera

- A Spot on the Banks of the Seine

- Water Lilies XIV

- Chrysanthemums IV

- The Road in Vetheuil in Winter

- The Pond at Montgeron II

- Dieppe

- Cap Martin

- The Church at Varengeville and the Gorge of Les Moutiers

- Rough Sea

- Farm near Honfleur

- The Boulevard des Capuchine

- Villas at Bordighera

- Windmills in Holland

- The Promenade at Argenteuil

- The Magpie

- Water Lilies Evening Effect

- By the River at Vernon

- Rouen Cathedral

- Le Lieutanance at Honfleur

- Spring Flowers

- Fisherman Cottage at Varengeville

- The Studio Boat

- The Lion Rock BelleIleenMer

- The Bay of Antibes

- Camille on the Beach at Trouville

- Palazzo Dario

- Still Life with Bottle Carafe Bread and Wine

- Meton Seen from Cap Martin

- The Tulleries

- Etretat Sunset

- Cap Martin III

- La Promenade

- Vetheuil in Summer

- Poppies near Vetheuilcirca

- Water Lilies 1907

- San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk

- The Walk Woman with a Parasol

- The Village of Lavacourt

- The Strollers study for Luncheon on the Grass

- Springtime through the Branches

- Olive Trees in Bordighera

- Plum Trees in Blossom at Vetheuil

- Water Lily Pond Symphony in Rose

- The Pink Skiff

- Water Lily Pond Water Irises

- Study of Olive Trees

- Branch of Lemons

- Water Lily Pond Evening right panel

- The Landing State

- The Banks of The Seine in Autumn

- The Valley of the Scie at Pouville

- Boats at Rouen

- Camille Monet in Japanese Costume

- The Artist’s House at Argenteuil

- Willows in Spring

- Snow Effect at Falaise

- The Castle at Dolceacqua

- The Valley of Sasso Bordighera

- The Artist’s Garden at Vétheuil

- Garden in Bordighera Morning Effect

- Antibes in the Morning

- Evening in the Meadow at Giverny detail

- The Manneport near Etretat

- The Water Lily Pond 1919

- Low Tide at Pourville

- Stormy Weather at Etretat

- Luncheon under the Canopy

- Valle Bouna near Bordighera

- Red Boats at Argenteuil

- Monet’s House in Argenteuil

- Boats in the Port of Honfleur

- The Pointe de la Heve at Low Tide

- Still Life with Pears and Grapes

- Sunlight Effect under the Poplars

- The House Seen from the Rose Garden II

- The Plain of Colombes White Frost

- Lavacourt Sun and Snow

- The Cliff at Dieppe

- The Rock Needle Seen through the Porte d Aumont

- The Esterel Mountains

- The Rose Bush

- La Japonaise Camille Monet in Japanese Costume

- Landscape with Figures Giverny

- Houses of Parliament London Sun Breaking Through the Fog

- Rouen Cathedral Portal in the Sun

- Boaters at Argenteuil

- Road to the SaintSimeon Farm

- Water Lilies X

- Spring Landscape

- Exterior of the Saint Lazare Station Arrival of a Train

- Field of Poppies at Giverny

- The Promenade at Argenteuil II

- Edge of the Cliff at Pourville

- Vetheuil Afternoon

- Bouquet of Sunflowers

- Pathway in Monets Garden at Giverny

- Amsterdam

- Banks of the Seine at Jenfosse Clear Weather

- Open Seacirca

- Gardener s House at Antibes

- The Beach at Trouville

- The Water Lily Pond left side

- The Cliff at Etretat

- Cliffs and Sailboats at Pourville

- Irises

- La Grenouillere

- Water Lilies VI

- Orange Branch Bearing Fruit

- Red Houses at Bjornegaard in the Snow Norway

- Agapanthus right panel

- On the Cliff at Fecamp

- The Garden Gate

- The Small Arm of the Seine at Mosseaux Evening

- The Boardwalk at Trouville

- Water Lilies XVI

- Boulevard St Denis Argenteuil Snow Effect

- The Studio Boat 1874

- In the Garden

- Pink Water Lilies

- Portrait Of Madame Gaudibert

- The Walk Argenteuil

- Women in the Garden

- The Church at Varengaville Grey Weather

- The Japanese Bridge VIII

- The Water Lily Pond III

- Two Grainstacks at the End of the Day Autumn

- The Ball Shaped Tree Argenteuil detail

- Bennecourt

- Water Lilies XIX

- Farmyard in Normandy

- Water Lilies IV

- Entrance to the Port of Trouville

- The Basin at Argenteuil

- The Gorge at Varengeville

- Water Lilies and Agapanthus

- Under the Lemon Trees

- Waves and Rocks at Pourville

- The Bridge over the Water Lily Pond

- Water Lilies VII

- Landscape at PortVillez

- Arm of the Seine near Vetheuil

- Relaxing in the Garden Argenteuil

- Road in a Forest

- The Seine at Asnieres

- Small Country Farm in Bordighera

- Calm Weather Fecamp

- Self Portrait with a Beret

- Camille in the Garden with Jean and His Nanny

- Vetheuil Pink Effect

- On the Cliff near Dieppe II

- The House Seen from the Rose Garden III

- A Windmill at Zaandam

- Poppies (Wild Poppies or The Poppy Field near Argenteuil)

- Evening Effect of the Seine

- The Big Blue in Antibes

- Wood Lane

- Ice Floes on the Saine at Bougival

- Woman with a Parasol Facing Right

- Yellow Irises

- The Fisherman s House at Varengeville

- Trees in Winter View of Bennecourt II

- Boatyard near Honfleur

- The Cliff Walk Pourville

- Impression Sunrise

- Windmills at Haaldersbroek Zaandam

- Jeanne-Marguerite Lecadre in the Garden (Woman in the Garden Sainte-Adresse)

- The Zaan at Zaandam II

- The Water Lily Pond aka Japanese Bridge

- BelleIle Rain Effect

- The Boats Regatta at Argenteuil

- The Rock Needle Seen through the Porte d’Aval

- Morning on the Seine near Giverny

- The Path through the Irises

- The Beach aka Camille Monet on a Garden Bench

- Poppy Fields near Argenteuil

- Water Lilies XI

- Autumn on the Seine at Argenteuil

- 4 The Water Lily Pond

- The Beach and the Falaise d Amont

- Rocks at BelleIle PortDomois

- Madame Gaudibert

- Two Trees in a Meadow

- Landscape at Vetheuil

- The Cliffs of Varengeville Gust of Wind

- Sunset left half

- Antibes Seen from the Salis Gardens

- Regatta at SainteAdresse

- Yachts at Argenteuil

- Weeping Willow Giverny

- Sunlight on the Petit Cruese

- Trees by the Seashore at Antibes

- The Flowered Garden

- Anglers on the Seine at Poissy

- Jean Monet on His Horse Tricycle

- The Rock Needle and Porte d’Aval Etrétat

- Sailing Boats at Honfleur

- Arm of the Seine near Giverny II

- The Railroad Bridge at Argenteuil II

- The Jetty of Le Havre in Rough Westher II

- Flowers and Fruit

- Palm Trees at Bordighera

- Fishing Boats

- The Steps

- The Grand Canal (Le Grand Canal)

- Water Lilies 2

- The Iris Garden at Giverny

- The Water Lily Pond

- Vetheuil Flowering Plum Trees

- Street in SaintAdresse

- Windmill at Zaandam

- The Cliff at SainteAdresse

- The House Seen through the Roses

- Bordighera Italy

- Riverbank at Argenteuil

- The Road to Vetheuil Snow Effect

- The Banks of the Seine at

- SainteAdresse

- The Valley of the Nervia

- Beach and Cliffs at Pourville Morning Effect

- Field of Tulips in Holland

- A Meadow

- Chrysanthemums III

- Three Poplars Trees in the Autumn

- Le Pave de Chailly

- Pine Trees Cap d Antibes

- Path in the Forest

- View of Bordighera

- The Banks of the Seine Lavacour

- Fecamp by the Sea

- Evening at Argenteuil

- Water Lilies II 1916

- Boat at Low Tide at Fecamp

- Camille Sitting on the Beach at Trouville

- The Seine near Bougival detail

- The Bridge at Argenteuil

- JuanlesPins

- Sunset on the Seine at Lavacourt Winter Effect

- Meadow with Poplars near Argenteuil

- The Banks of the Seine Ile de la GrandeJatte

- The Seine at Argenteuil

- Argenteuil Seen from the Small Arm of the Seine

- Poplars on the Banks of the River Epte at Dusk

- The Avenue

- Customs House Rose Effect

- Water Lilies 1904

- The Water-Lily Pond 1897 (Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge)

- Water Lilies II

- Exterior of Saint Lazare Station aka The Signal

- The Robec Stream Rouen aka Factories at Deville near Rouen

- White Frost

- The Flowered Arches at Giverny

- The Hoschedes Garden at Montgeron

- Villas in Bordighera

- Garden of the Princess

- The Seine near Vernon

- Hotel des Roches Noires Trouville

- 4 The Seine near Giverny

- The Parc Monceau

- Etretat Rough Sea

- Alice Hoschede in the Garden

- Water Lily Pond with Irises

- The Moreno Garden at Bordighera II

- Pourville near Dieppe

- The Willow aka Spring on the Epte

- Antibes Seen from the Salis Gardens II

- The Riverbank at Petit Gennevilliers

- The Seine near Vetheuil Stormy Weather

- The Banks of the River Epte in Spring

- At Cap d Antibes

- The Main Path at Giverny

- Fontainebleau Forest

- The Luncheon (The Lunch decorative panel)

- Bend in the River Epte

- Haystacks at Giverny

- Poplars on the Banks of the River Epte Seen from the Marsh

- Coastal Road at Cap Martin near Menton

- View of Ventimiglia

- Train in the Snow the Locomotive

- The Banks of the Seine at Argenteuil

- Group of Rocks at PortGoulphar

- The Flood of the Seine at Vetheuil

- Strada Romada in Bordighera

- A Cart on the Snow Covered Road with SaintSimeon Farm

- Oat and Poppy Field Giverny

- The Water Lily Pond detail

- Morning on the Seine Clear Weather

- Lavacourt

- The Cliff near Dieppe

- Four Trees

- Poplars View from the Marsh

- Tree in Flower near Vetheuil

- The Beach at Trouville II

- Zaandam

- Water Lilies 1906

- Poplars Wind Effect

- The Road from Vetheuil

- An Orchard in Spring

- Woman with a Parasol

- Willows at Sunset

- Waves Breaking

- The Rocks at Pourville Low Tide

- Poplars on the Banks of the River Epte

- Fog Effect

- Cliffs of Les Petites Dalles

- The Seine near Giverny

- Morning on the Seine 1897

- Dolceacqua

- Garden in Flower

- Still Life with Melon

- Boulevard of Capucines

- Tow Path at Lavacourt

- Exterior of Saint Lazare Station Sunlight Effect

- Quai du Louvre

- The Mediterranean aka Cam d Antibes

- Antibes Seen from the Cape Mistral Wind

- Morning on the Seine Clear Weather II

- Sunrise (Marine)

- Morning on the Seine in the Rain

- Yellow and Lilac Water Lilies

- The Bridge in Monet s Garden

- Argenteuil Flowers by the Riverbank

- Fruit TreesNo dates listed

- The Valley of Sasso Sunshine

- The Garden Gladioli

- The Mill at Vervy

- Morning rightcenter detail

- The Valley of Sasso Blue Effect

- Sunset right half

- The Jetty at Le Havre II

- Poppy Field in Giverny

- Canal in Amsterdam

- Agapanthus center panel

- Le Rue de La Bavolle at Honfleur II

- Still Life Red Mullets

- The Dike at Zaandam Evening

- The Church at Varengeville

- In the Woods at Giverny Blanche Hoschedé at Her Easel with Suzanne Hoschedé Reading

- Springtime

- The Seine at PortVillez Blue Effect

- Mouth of the Seine at Honfleur

- Water Lilies

- View of Argenteuil in the Snow

- Les Roches at Falaise near Giverny

- Flowers at Vetheuil

- The Cliffs of Les PetitesDalles

- Road at Louveciennes Melting Snow Sunset

- Green Reflection right half

- The Water Lily Pond II

- The Alps Seen from Cap d Antibes

- The Japanese Footbridge

- Young Girls in a Row Boat

- Poplars on the Banks of the River Epte in Autumn

- The Artist s House at Giverny

- The Blue House at Zaandam

- Monte Carlo Seen from Roquebrune

- Water Lilies III

- Boats on the Beach

- Yellow Irises II

- The Japanese Bridge

- The Sea in Antibes

- Water Lilies XII

- Apple Trees on the Chantemesle Hill

- BelleIle Rocks at PortGoulphar

- The Pyramids at PortCoton

- On the Coast at Trouville

- Path

- The Japanese Bridge 2

- Houses on the Zaan River at Zaandam

- Regatta at Argenteuil

- Farmyard

- Clamatis

- Under the Pine Trees at the End of the Day

- The Banks of the Seine at PortVillez

- The Shoot

- Victor Jacquemont Holding a Parasol

- Entering the Village of Vetheuil in Winter

- Lane in the Vineyards at Argenteuil

- The Artist s Family in the Garden

- The Custom House Morning Evvect

- Poplars near Giverny Overcast Weather

- The Point de la Heve Honfleur

- The Road from Chailly to Fontainebleau

- Springtime (The Reader or Woman Reading)

- The Seine near Giverny 1897

- Beach in JuanlesPins

- Two Anglers

- View near Rouelles

- The Riverbank at Le Petit Gennevilliers Sunset

- The Path at La Cavee Pourville

- The Doges Palace

- A Palm Tree at Bordighera

- The Bodmer Oak Fontainebleau

- Antibes Seen from the Salis Gardens III

- At Les PetitDalles

- Young Girl in the Garden at Giverny

- The Boardwalk on the Beach at Trouville

- Giverny in Springtime

- Morning Landscape Giverny

- Vase of Peonies

- Poplars in the sun (Three Poplar Trees Autumn Effect)

- SaintGermainl Auxerrois

- Morning on the Seine

- Sailboats at Sea Pourville

- Hauling a Boat Ashore Honfleur

- Fishing Boats at Sea

- The Steps at Vetheuil

- Asters

- Snow Effect at Limetz

- Poppy Field near Vetheuil

- Poplars White and Yellow Effect

- SaintAdresse Beached Sailboatcirca

- Bouquet of Mallows

- Water Lilies 1905

- Monet s Garden at Vetheuil

- On the Beach at Trouville

- The Seine at Bennecourt in Winter

- Pleasure Boats

- The Isle La Grande Jatte

- Bed of Chrysanthemums

- Venice, Palazzo Dario

- The Sheltered Path 1873

- Three Trees in Autumn

- Camille Embroidering

- The Bridge at Argenteuil

- Water Lilies IX

- 4 The Studio Boat

- The Windmill on the Onbekende Canal Amsterdam 1874

- Fishing Boats by the Beach and the Cliffs of Pourville

- Fruit Basket with Apples and Grapes

- The Red Road near Menton

- The Seine at Vetheuil II

- Morning on the Seine near Giverny

- The Japanese Bridge at Giverny

- Rising Tide at Pourville

- Breakup of Ice Grey Weather

- The Seine at Rouen

- At the Parc Monceau

- Garden at Sainte-Adresse

- Sunset on the Seine in Winter

- The Sea at Fecamp

- Path along the Water Lily Pond

- Cliffs at Pourville in the Fog

- 5 The Seine at Vetheuil

- San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk (Twilight Venice)

- The Artist s Garden at Vetheuil

- Coming into PortGoulphar BelleIle

- By the Sea

- Lighthouse at the Hospice

- The Road to Monte Carlo

- Haystack at Giverny

- Luncheon on the Grass

- Three Fishing Boats

- The Thames below Westminster

- Poplars on the Banks of the River Epte Overcast Weather

- Vetheuil Seen from Ile Saint Martin

- The Stoller Suzanne Hischede

- The Fonds at Varengeville

- Bridge at Dolceacqua

- Road to Giverny in Winter

- The Towpath at Granval

- Stormy Seascape

- Woodbearers in Fontainebleau Forest

- The Grand Canal and Santa Maria della Salute

- The Japanese Footbridge, Giverny

- Argenteuil the Hospice

- The Zaan at Zaandam

- Still Life Apples and Grapes

- The Bridge at Bougival

- Cliff at Etretat (La Porte d’Amont Étretat)

- View of Antibes from the Plateau

- Houses of Parliament Sunset II

- Infantry Guards Wandering along the River

- Pyramids at PortCoton

- Cap Martin II

- Bennecourt 1887

- Rio della Salute II

- The Olive Tree Wood in the Moreno Garden

- The Tea Set

- Fishing Boats Leaving the Port of Le Havre

- Bouquet of Gadiolas Lilies and Dasies

- The House among the Roses

- WaterLilies

- Water Lily Pond with Irises left half

- The Beach at Fecamp

- The Church at Varengeville against the Sunset

- View of the Old Outer Harbor at Le Havre

- Springtime aka Apple Trees in Bloom

- 3 Water Lilies II

- Camille Monet in the Garden at the House in Argenteuil

- Misty morning on the Seine blue

- The Old Rue de la Chaussee Argenteuil II

- Beach at Etretat

- Haystacks Overcast Day

- Cliff near Fecamp

- Argenteuil Seen from the Small Arm of the Seine

- The Green Wave

- San Giorgio Maggiore

- Canal in Zaandam

- Rue Saint-Denis in Paris Celebration of 30 June 1878

- Agapanthus

- Yellow Irises with Pink Cloud

- Irises II

- Leicester Square at Night

- Boats in the Port of London

- Three Pots of Tulips

- Agapanathus

- Irises III

- Fishing Boats off Pourville

- Sailboat at Le Petit Gennevilliers

- Bathers at La Grenouillere

- Water Lilies XV

- Water Lilies Reflections of Weeping Willows right half

- Landscape at Giverny

- Hamerocallis

- Yellow Irises III

Singing Palette

Singing Palette